Imaginary voyages : Picasso and the Ballets Russes

Between Italy and Spain

Mucem, fort Saint-Jean—

Fort Saint-Jean Georges Henri Rivière Building (GHR) 320 m2

|

From Friday 16 February 2018 to Sunday 24 June 2018

From the Mucem to the Centre de la Vieille Charité, Picasso, Imaginary Voyages is the major exhibition of 2018 in the museums of Marseille.

At the Mucem, the exhibition is presenting the exhibition Picasso and the Ballets Russes, between Italy and Spain.

Picasso’s strong links with popular arts and traditions were highlighted in spectacular fashion in his stage designs and costumes for Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes company.

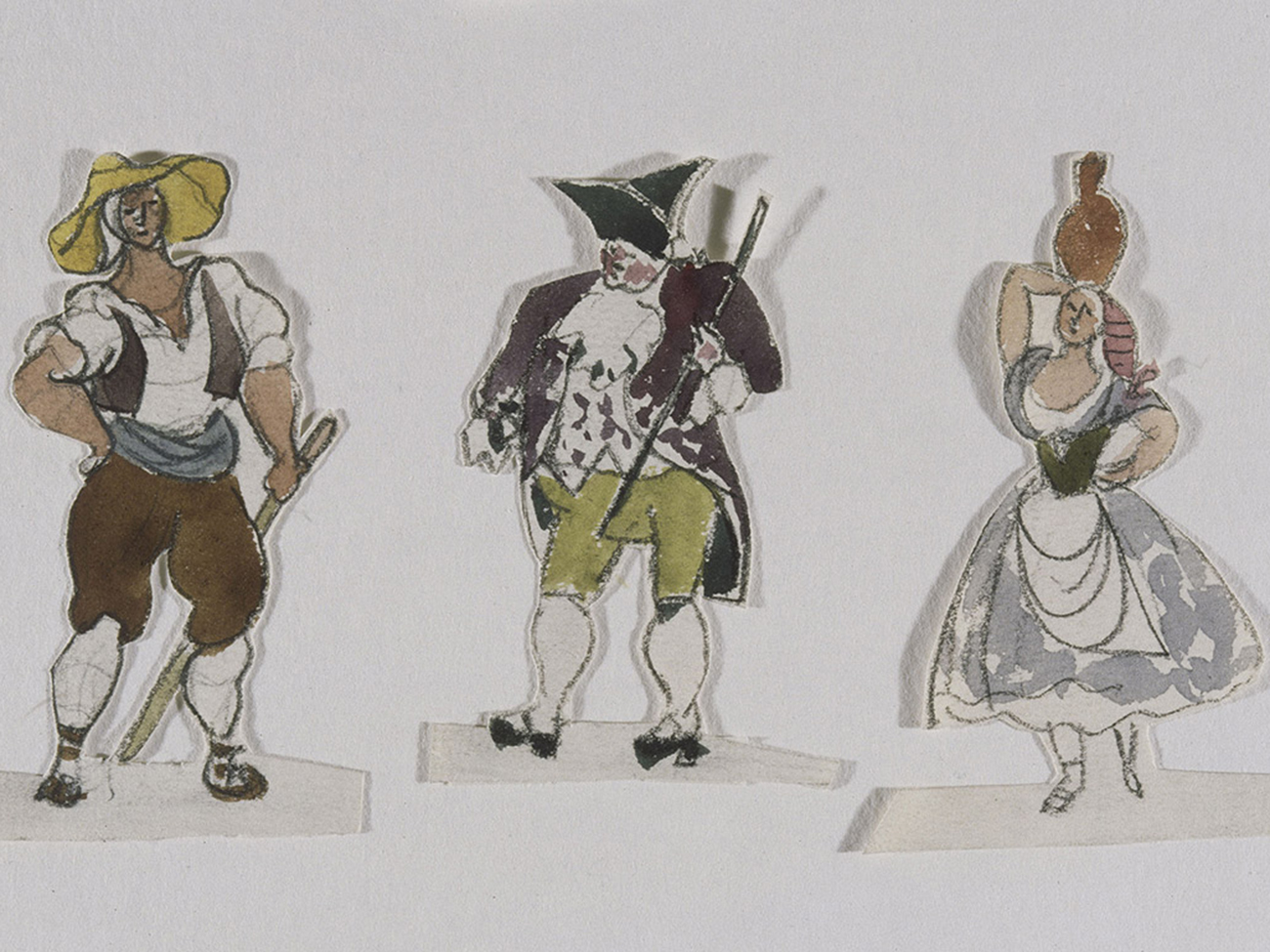

Between 1916 and 1921, Picasso collaborated on four productions for which he created the sets and costumes: the ballets Parade (1917), Tricorne (1919), Pulcinella (1920) and Cuadro Flamenco (1921). The experience brought the painter into contact with the language of the body and dance, inspiring him to explore new formal possibilities, which he combined with elements borrowed from puppet theatre, commedia dell’arte, sacred art and Spanish folklore.

Juxtaposing works by the artist (canvases, drawings, sketches, models, costumes) with objects from the Mucem’s collections, the exhibition reveals how Picasso was able to assimilate and reinterpret the figurative traditions of his time, placing them at the heart of a new form of modernity.

Curators: Sylvain Bellenger, General Director of the Museo di Capodimonte; Luigi Gallo, art historian; Carmine Romano, art historian

Exhibition design: Dodeskaden

At the Centre de la Vieille Charité, the exhibition brings together more than one hundred masterpieces – paintings, sculptures, assemblages, drawings – in juxtaposition with the artist’s collection of postcards and key works from Marseille’s museums. It reflects the breadth of Picasso’s curiosity, sharpened by his boundless desire to discover cultures other than his own.

The starting point for this imaginary journey was Marseille in 1912, where Picasso bought the African masks that would exert a crucial influence on his work.

The exhibition travels to five destinations, embracing voyages both real and imagined: Bohème Bleue, Afrique fantôme, Amour antique, Soleil noir and Orient rêvé, all journeys into Picasso’s imagination: ‘If all the ways I have been along were marked on a map and joined up with a line, it might represent a minotaur.’

The highlight of the exhibition, the sculpture Les Baigneurs, is displayed at the centre of the majestic setting of the Chapelle de la Vieille Charité, creating a new dialogue between Picasso’s theatrical designs and Pierre Puget’s Baroque architecture.

Curators: Xavier Rey, director of the Musées de Marseille; Christine Poullain, honorary director of the Musées de Marseille; Guillaume Theulière, assistant curator at the Musées de Marseille

Exhibition design: e.deux - Etienne Lefrançois, Emmanuelle Garcia

-

Interview with Carmine Romano, co-curator of the exhibition at the Mucem.

-

Mucem

This exhibition presents a little-known aspect of Picasso’s work, that of stage and costume designer for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes between 1916 and 1921. What was the background to this collaboration?

Carmine Romano Through a series of coincidences, some of the most interesting figures in Paris during those years, notably Cocteau, Satie, Diaghilev, Massine and Picasso, decided to collaborate on the creation of a new ballet, which promised to be revolutionary. It was the summer of 1916, and their work on the ballet Parade, performed on 18 May 1917, coincided with the blossoming of a friendship between Picasso and Cocteau – one that would last their whole lives – but also of a professional relationship and friendship between the Spanish painter and Diaghilev, which would allow the latter to give free rein to his ‘natural instinct’ for theatre.

Diaghilev, the representative of Russian modernity in Paris, obviously hoped to encapsulate the Parisian avant-garde embodied by Picasso: he thereby achieved the feat of introducing the Parisian elite to the world of Montmartre, which was the epicentre of contemporary art.

Mucem Among Picasso’s main creations for the Ballets Russes is the famous curtain for Parade.

C.R. Since the curtain for Parade is currently on display in Rome, in the exhibition ‘Picasso, between Cubism and Classicism, 1915–1925’, we will be exhibiting a copy at the Mucem. An interactive screen will enable us to explore its history and iconography. Indeed, we have made some discoveries in relation to this curtain, including the identities of the figures depicted, and the elements that inspired Picasso to create it.

In Diaghilev’s biography, we learn that at the premiere of Parade, when this painting by Picasso was unveiled, many members of the public, convinced that the Spanish artist was playing a practical joke, thought they recognised the figures painted on this curtain. In particular, the Moor with the turban, who appeared to be a portrait of Stravinsky, and the Neapolitan sailor, who closely resembled Diaghilev.

Since then, several researchers (Rothschild and Axsom among others) have attempted to identify the figures on this curtain. In the exhibition at the Mucem, with the aid of new technology and a collection of documents and archive photos, we will be comparing the figures painted on the curtain with portraits of those people in Picasso’s entourage working on the ballet Parade. We will thus be able to propose an identity for each of the figures depicted on this curtain.

Mucem The exhibition also shows Picasso’s work for the ballets Tricorne (1919), Pulcinella (1920) and Cuadro Flamenco (1921). For Picasso, they were all opportunities to express his affinities with popular arts and cultures?

C.R. Exactly. All the Ballets Russes productions that Picasso collaborated on were marked by a desire, on the part of both artists and musicians, to explore the sacred territory of the popular arts and traditions.

Picasso did not really like the term ‘popular art’, which emerged at that time, and which would be developed by Georges Henri Rivière. He preferred to talk simply of ‘art’, even going as far as to say: ‘There is no popular art, only art.’

In the ballets Parade and Pulcinella, which can be described as Italian on account of their clear references to the city of Naples, as in the Spanish ballets Tricorne and Cuadro Flamenco, Picasso explored all the elements of traditional theatre, appropriating popular conventions, which he redeveloped and created a new form of modernism around.

Mucem What are the themes that recur in these works?

C.R. As you highlighted in your previous question, these themes were rooted in popular forms of art and dance, in puppet theatre and the commedia dell’arte. The recent discovery of Neapolitan crafts items and pupi siciliani (Sicilian puppets) belonging to the artist sheds light on a fundamental aspect of the artistic and theatrical output of this period, concerning not only Picasso but also Cocteau, Apollinaire and numerous European intellectuals who regarded contemporary theatre as being rigid and sterile. They were more interested in less ‘bourgeois’ forms like the circus, popular dances and, of course, puppet theatre and the commedia dell’arte. We know of the letters that Picasso sent to Apollinaire after seeing puppet shows at the Teatro dei Piccoli in Rome, and the postcard sent by Cocteau to his mother during his trip to Naples, in which he describes the performance of the pupi siciliani and says the puppets were more believable than flesh and blood actors.

These themes can easily be seen in the ‘gestural dance’, in part mimed, of Parade, as well as in Pulcinella and Tricorne (which, as originally conceived, were ballet pantomimes).

It’s also important to present the Spanish themes that were so dear to the painter and which were linked to his childhood and above all his father: the corrida and flamenco. The work that was centred on folk music and traditional dance turned out to be crucial in the Spanish ballets.

There is an example in Tricorne, where the corregidor, a sort of court magistrate, is seduced by the miller’s wife, who dances a sensuous fandango for him, an Andalusian folk dance, a forerunner of flamenco. Finally, a corrida was painted on the curtain for Tricorne, of the kind that the young Pablo could see from the terrace of the house of his uncle, Salvador.

Mucem In what way do Picasso’s designs for the Ballets Russes reflect his development as an artist?

C.R. Firstly, it should be pointed out that Picasso’s collaboration with the Ballets Russes coincided with one of the most important periods of his life. From a personal point of view, it was while he was working on Parade that Picasso met the dancer Olga Khokhlova, with whom he fell in love, marrying her in 1918. It was also one of the rare times that he lived outside France: in 1917, Picasso stayed for just over two months in Rome, then for a few months in Spain.

It was a very rich period for the artist, one that historians often associate with the end of the Cubist period and a sort of return to normality, towards a new classicism. But the reality may have been a bit more complex. I think that from a stylistic point of view, his stage design work for the Ballets Russes, thanks to his conception of the stage as space and use of large-scale perspective, enabled him to extend his experiments with sculptural assemblages, a central aspect of Cubism.

Mucem What major works are on display in this exhibition?

C.R. Besides the drawings for sets, curtains and costumes produced by Picasso for the Ballets Russes, we are displaying the painting La Loge, created for the ballet Cuadro Flamenco, which was cut up and sold by Diaghilev, before being rediscovered quite recently and exhibited by the Pinacoteca di Brera.

To reflect his great love of commedia dell’arte and popular art, we are exhibiting a few pieces that belonged to Picasso, from the Faba collection, such as the two Pulcinellas in the photograph Olga assise au piano, taken by the artist in 1920, as well as his own reinterpretation of the same figure, for which he deconstructed and recreated the mask.

In addition, visitors will be able to see the spectacular Cubist costumes for Parade made by the Rome Opera and the more classical ones for Pulcinella and Tricorne. A series of archive films never screened before, together with original photos, will enable us to travel through time, to the period when these ballets were created, plunging us into the artistic climate of the period.

This exhibition, which I’m co-curating with Sylvain Bellenger and Luigi Gallo, seems to be a project that is tailor-made for the Mucem and its collections. We have selected a number of objects from the museum’s vast collections that illustrate Picasso’s sources of inspiration linked to popular arts and traditions: puppets, theatre sets, posters, ex-votos. By juxtaposing these objects with Picasso’s works, the exhibition highlights the genius of this artist who was able to appropriate elements from the world around him and, simultaneously, reconfigure them with the playful, carefree spirit of a child.

Special offer

Ticket for 2 Picasso ‘Voyages imaginaires’ exhibitions: €15

Single price for 1 person, from 16 February to 24 June 2018, on sale only at Mucem and Vieille Charité

Partners and sponsors

Picasso-Mediterranean, an initiative by the Musée National Picasso-Paris.

This exhibition was supported by the Musée National Picasso-Paris and is part of the international cultural event ‘Picasso-Méditerranée 2017–2019’. More than sixty institutions have jointly created a programme around Picasso’s ‘obstinately Mediterranean’* work. Initiated by the Musée National Picasso-Paris, this journey through the artist’s work and the places that inspired him offers a new cultural experience aimed at reinforcing links between the two shores. (*Jean Leymarie)

In partnership with the SNEF group