Made in Algeria

Genealogy of a territory

Mucem, J4—

Niveau 2

|

From Wednesday 20 January 2016 to Sunday 8 May 2016

The exhibition Made in Algeria, Genealogy of a Territory is the result of a close collaboration between the Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art (INHA), the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BnF) and the Musée des Civilisations de l’Europe et de la Méditerranée (Mucem).

It is the first major exhibition devoted to the representation of a territory, Algeria.

Made in Algeria demonstrates how cartographic invention accompanied the conquest of Algeria and its description.

The exhibition gathers an ensemble of maps, drawings, paintings, photographs, films and historical documents as well as works by contemporary artists who have surveyed the Algerian landscape. Nearly 200 pieces are being presented from major museums in France and abroad including new contemporary creations… A collection of original maps of rare aesthetic quality is being presented to the public for the first time.

Made in Algeria, Genealogy of a Territory is an exhibition devoted to cartography and to its development, for which the French conquest and expansion into Algeria was the driving force. Beyond the topographic interest and the aesthetic beauty of the maps presented in the exhibition, the need to account for the genealogy of this adventure, and the political subjectivity of which it was a part, is mandated. The blank spaces on maps played a major role in the invention of the territory, its cultural orientation and the narrative to follow. The latter long prevented any possibility of seeing the way of life and the past of the inhabitants of this country otherwise.

The Algerian war is not the subject of the exhibition. Rather, it is what took place prior to this war that is presented. Made in Algeria, Genealogy of a Territory seeks to report, through images, cartography and field surveys, on this long and singular process that was, in truth, the impossible conquest of Algeria. Conflicts, even residual, were unceasing during the entire period of colonisation.

This exhibition is devoted to representations of a country and its lands, Algeria. It is an attempt to lay bare a modern adventure that began more than two hundred years ago and whose effects persist today: the colonial manufacturing of a territory.

When the French landed at Sidi Ferruch in June 1830, they knew very little about the territory of the Ottoman Regency. For the Europeans, the sole priority was the long coastal fringe. Then, from the conquest of Algiers at the end of the war against Abd el-Kader, Algeria became the domain of the military. As the Army of Africa conquered the Algerian territory, the imagery did not fail to take hold of the numerous expeditions shaping a vision of this territory. This vision was further developed, through the highly symbolic naming of places. Everywhere, and until independence, indigenous names were replaced by new names given to the centres of colonisation and Algerian cities. Later, this representation would be used for other objectives as Todd Shepard demonstrates in his contribution to the catalogue: from the late 19th century until 1962, commentators would describe Algeria as a land of expansion, a “frontier” intended to revitalise France. For more than a century, this country was a major laboratory in the domains of agriculture, tourism, architecture, science and territorial surveillance. After independence, the construction of the image of the Algerian territory and its self-representation remain an extremely complex process.

This major exhibition inaugurates a novel history of the representation of Algeria in France. The contemporary works featured in the exhibition are new for the most part. They are by Louisa Babari, Mohammed Dib, Hassen Ferhani, Mostafa Goudjil, Katia Kameli, Mohamed Kouaci, Gaston Revel, Dalila Mahdjoub, Jason Oddy, Raphaëlle Paupert-Borne, Zineb Sedira, Ahmed Zir, and Hellal Zoubir. They give life to another account of the conquest, part of a controcampo, which could be that of the Algerian people, for the quality of the heritage presented cannot obscure the burden of what it has erased.

The exhibition is divided into four parts:

- Seen from afar - A territory viewed from the sea before 1830

- Charting the territory – From conquest to colonisation - after 1830

- Conquering Algeria - From excessive imagery to the end of French Algeria

- From up close- Glimpses of Algeria after 1962

Bearer of the need to present to the public this sensitive and unique heritage, which can only provide a better understanding of the present, the exhibition has greatly benefited from the unfailing generosity of public collection managers and from their moral and ethical support in meeting the cultural, historical, and political challenges of such an exhibition. Their participation has been crucial and must be mentioned, especially given the exceptional collections on Algeria that they contributed: the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, the Musée National des Châteaux de Versaille et de Trianon, the Service Historique de la Défense in Vincennes, the Musée de l'Armée, the Archives Nationales d’Outre-Mer and the archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affaires and International Development; as well as the Greenwich National Maritime Museum in London and the Musée Boucher-de-Perthes in Abbeville, and various private collections: the holdings of the Éditions Baconnier, the Centre Diocésain des Glycines in Algiers, and the photographic collections of Gaston Revel, Mohammed Dib and Mohamed Kouaci.

Temporary exhibition organised by the MuCEM, in collaboration with the Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art and the Bibliothèque Nationale de France

General Commissioners:

Zahia Rahmani, Head of the research programme “Arts and Globalisation” at the Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art

Jean-Yves Sarazin, Director of the Department of Maps and Plans at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Scenography: Cécile Degos

The catalogue reflects the history of the Algerian territory through an ensemble of previously unpublished texts and essays by Nacéra Benseddik, Hélène Blais, Daho Djerbal, François Dumasy, Nadira Laggoune, Zahia Rahmani, Jean-Yves Sarazin, Nicolas Schaub, Todd Shepard, Fouad Soufi and Sylvie Thénault.

An exceptional collaboration was brought to bear for Made in Algeria from three national institutions: the BnF, the INHA and the MuCEM. The exhibition benefited during its development from the generous support of the authorities of the People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria, and its Ministry of Culture and the French Embassy in Algiers.

Exhibition itinerary

1: Seen from afar - A territory viewed from the sea before 1830

Hall 1: Seen from afar

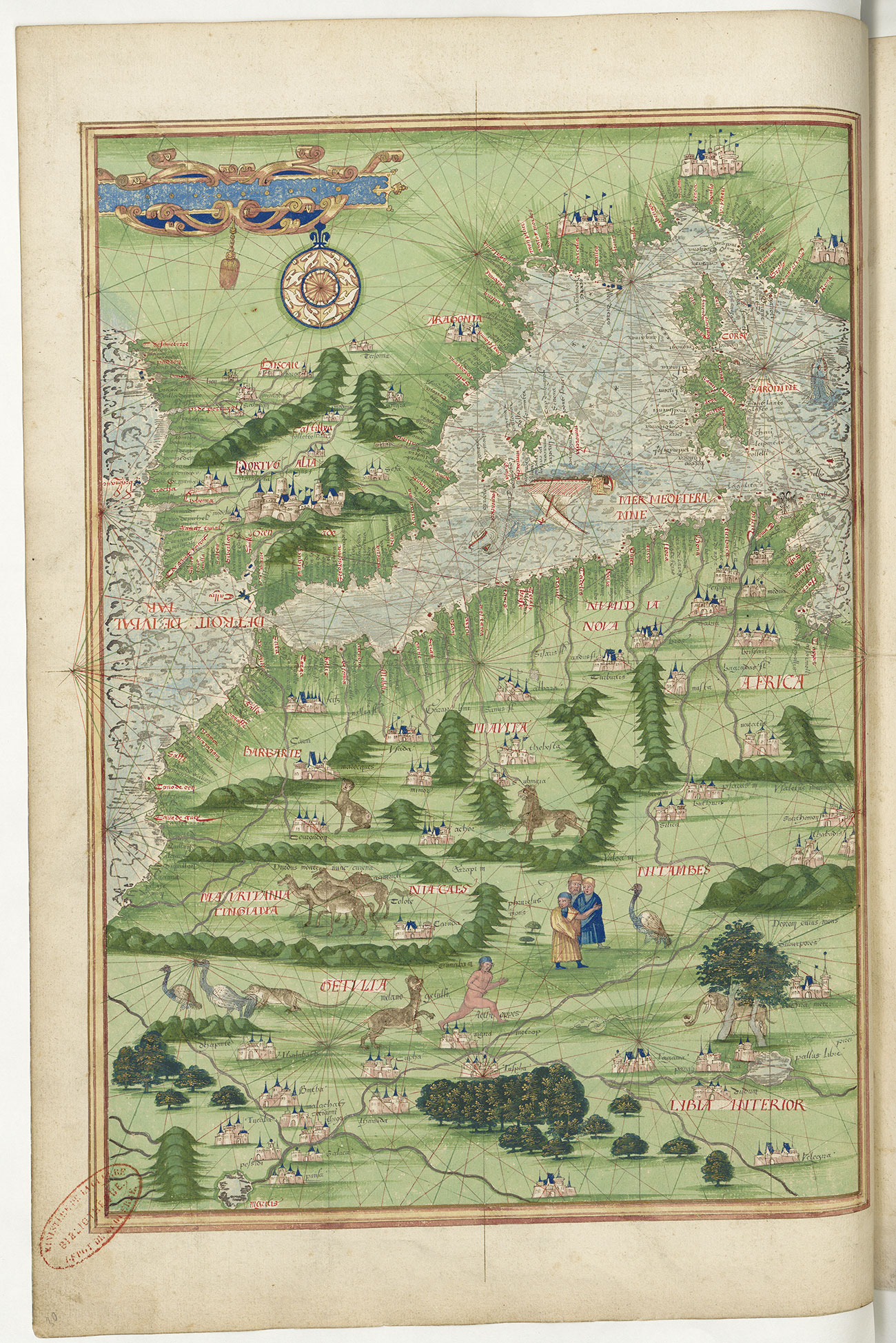

Algeria has seen the passage of numerous civilisations. In Antiquity, North Africa was largely part of the Kingdom of Numidia. The territory played an important role under the Roman, then Christian and Muslim Empires where the local populations experienced the contributions of many migrations. For several years, maps did not designate the Algerian coastline as a zone foreign to the European world.

With the fall of Granada in 1492 and the expulsion of the Moors from Spain to North Africa, a belligerent relationship developed between the kingdoms and states of the West and the Kingdom of Tlemcen and then that of the Ottoman Regency of Algiers from 1515 to 1830. The name Barbary or Berbery/Berberia thus replaced the terms Mauritania and Numidia, which designated the northern African continent on maps.

Algeria is bordered by a coastline of more than 1600 km, which is dominated by the slopes of the Tell Atlas from east to west with its high plateaus and lowland plains, until its natural border, the Saharan Atlas. It is the largest country in Africa. The exhibition demonstrates how the cartographic delineation of this territory occurred over several decades.

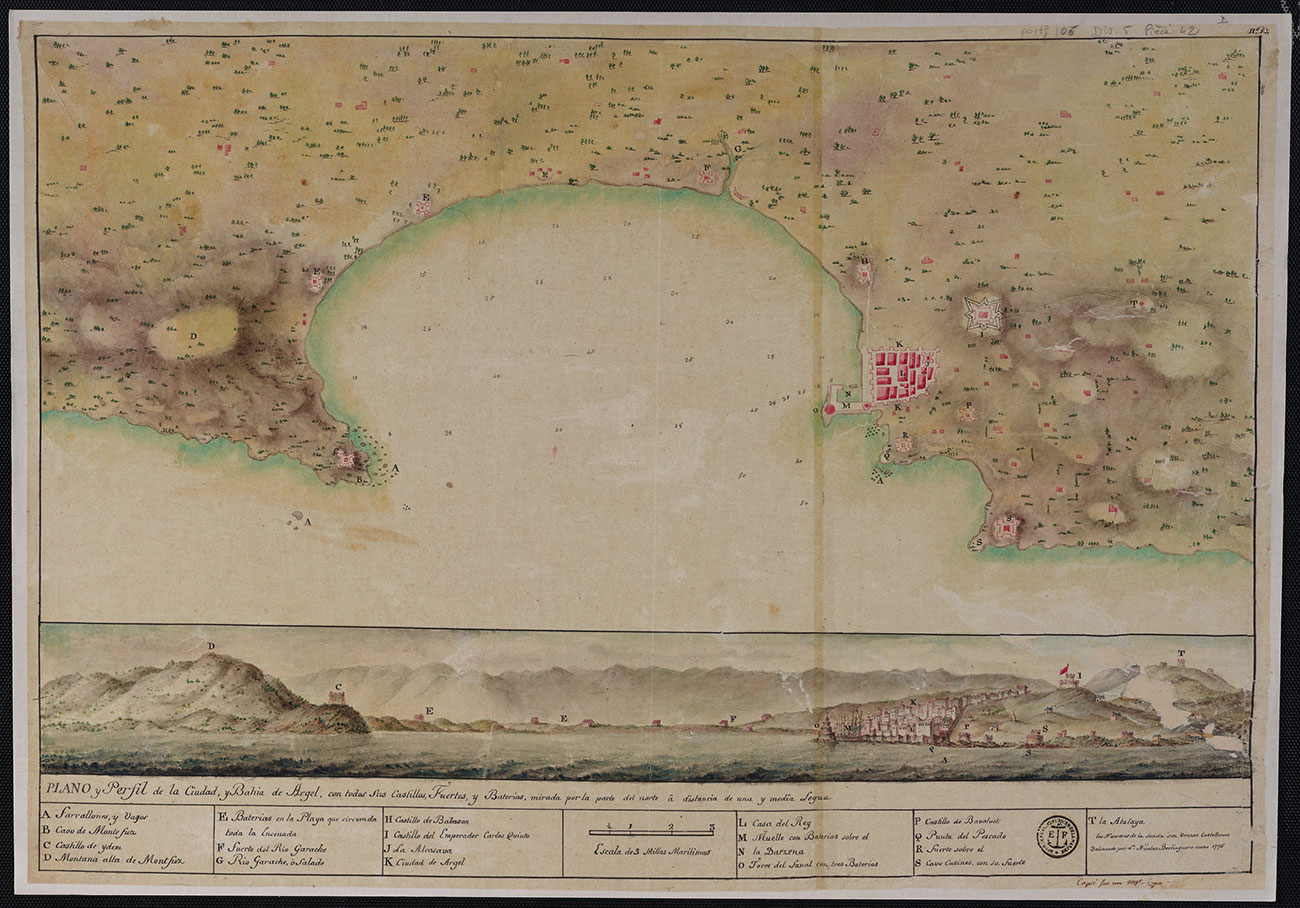

Handwritten map, Nicolas Berlinguero, Plano y Perfil de la Ciudad, Bahia de Argel, 1775 :

Over the course of the 18th century, the European nations of Spain, the United Provinces of the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and France became interested, under economic pretexts, in the Ottoman Regency of North Africa. This handsome but complex handwritten document, combining the plan of the bay of Algiers with its profile while viewed from the sea, would have been disseminated by engraving so sailors could more easily appropriate the coastline and navigate safely.

Hall 2: Seen from afar, View from the sea

The territories of North Africa were not unknown to Europeans before 1830.

Merchants and travellers frequented them freely, even though the risk persisted of being taken captive and ransomed.

Numerous accounts circulated, including approximate or more detailed descriptions, all the more so after the development of printing (invented in 1454) enabled their reproduction and diffusion.

However, given the conflicted relationship maintained on both sides, Europeans considered the Barbary Coast/Algeria and its port cities as zones where circulation was risky. The Regency threatened France less, however, than other Christian kingdoms.

Algiers and its fortifications underwent sieges and bombardments from 1541 to 1830, thus it is not surprising that some of the geographical maps and topographical plans representing the territory and its surroundings are from a warlike perspective.

Argel, location unkown, 17th century, handwritten map:

This perspective view of the bay of Algiers, neither signed nor dated, depicts the landing of an armed expeditionary force at the mouth of the Oued El Harrach or the future Great Mosque of Algiers, today completely urbanised. Argel is the Spanish name for Algiers and the three-masted vessels date from the second half of the 16th century. Is it a souvenir of the daring invasion by Charles V who landed in 1541 on the beach of Hamma (Jardin d’Essai) on 23 October?

Hall 3: Seen from afar, The interior emerges

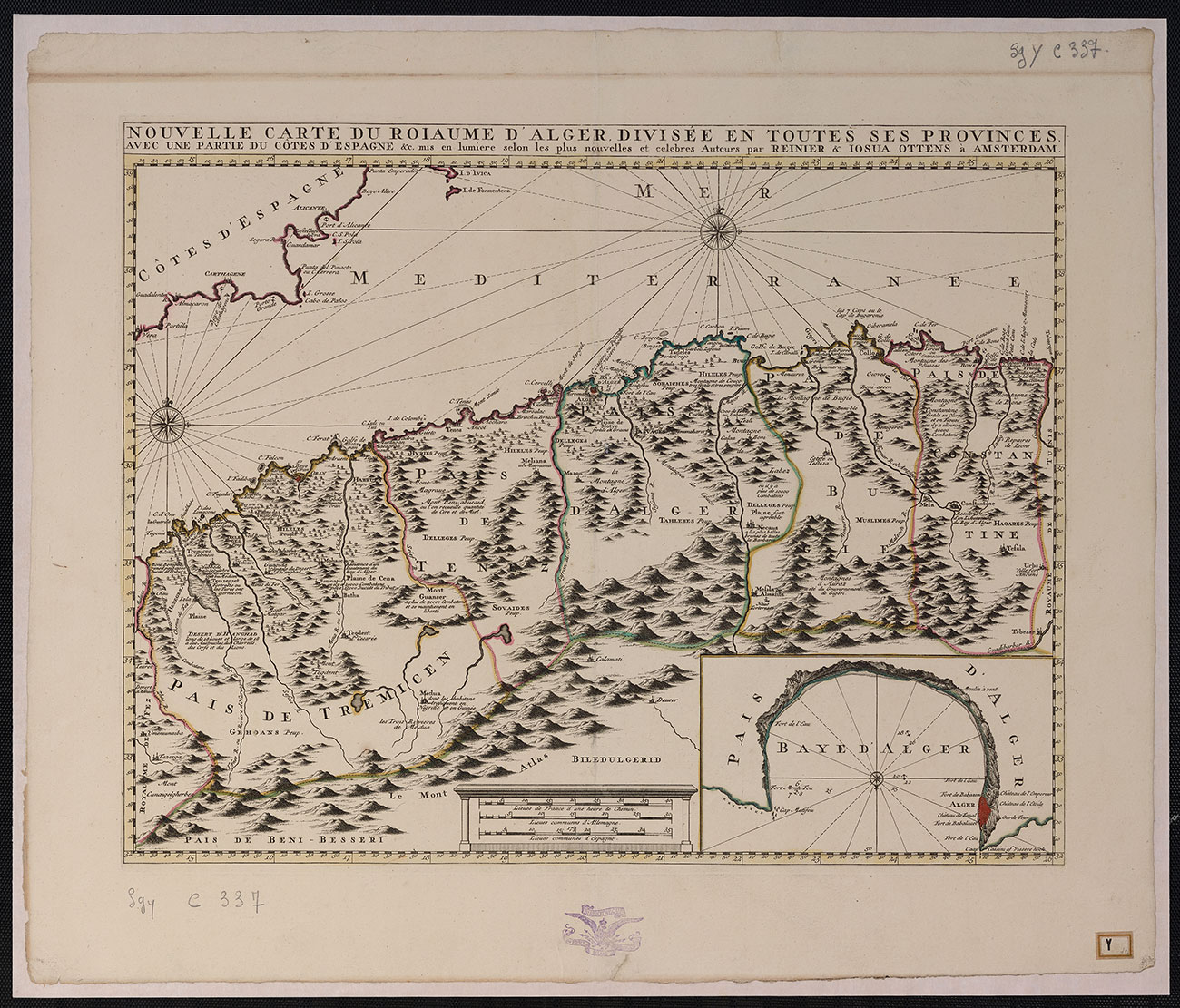

From the 18th century onward, maps depicted a precise view of the territory. If inaccuracies persisted in describing interior lands, the maritime fringe with its coastline and seashore was, however, quite well understood by the end of the century.

Cartographic innovation in maritime representation was a prerequisite for the improvement of civil and military navigation. Boats loaded with goods from Algiers, Oran, La Calle (El Kala) sailed towards all the Mediterranean ports and every navigator or inexperienced sailor used these new navigation tools.

Inland, the Geography treatise by the English scholar and chaplain Thomas Shaw, published in Oxford in 1738, marked all subsequent work until 1830. Similarly, the precious notes taken by the spy Vincent Yves Boutin in 1808, secretly kept by the military at the Dépôt de la Guerre, were crucial at the moment of the invasion of June 1830

Argel,location unknown, 17thcentury, handwritten map, Reinier et Losua Ottens :

This perspective view of the bay of Algiers, neither signed nor dated, depicts the landing of an armed expeditionary force at the mouth of the Oued El Harrach or the future Great Mosque of Algiers, today completely urbanised. Argel is the Spanish name for Algiers and the three-masted vessels date from the second half of the 16th century. Is it a souvenir of the daring invasion by Charles V who landed in 1541 on the beach of Hamma (Jardin d’Essai) on 23 October?

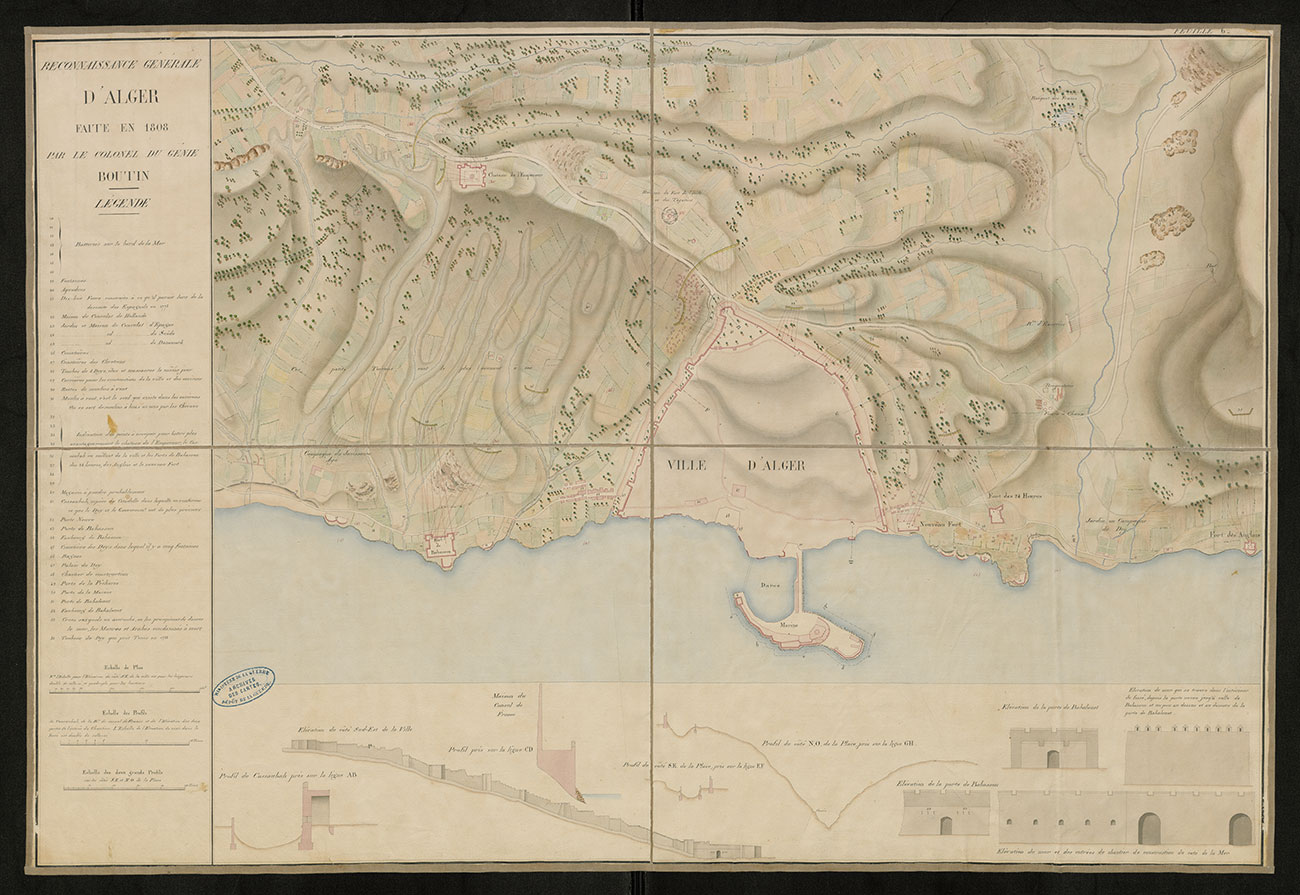

Carte manuscrite 1808, Vincent Yves Boutin, Reconnaissance générale d’Alger faite en 1808 :

Ten years after General Bonaparte led the Egyptian expedition, he became emperor and hoped to establish a foothold in Algeria. He commissioned a report from his minister of the navy, Decrès, on the city of Algiers and its surroundings. Vincent Yves Boutin, a mining engineer and outstanding observer of the geography of the places visited, provided this secret account. From May to July 1808 he wandered, Shaw’s book in hand, around Algiers to Sidi Ferruch, which he recognised as the only possible landing site for an expeditionary force.

2: Charting the territory – From conquest to colonisation - after 1830

Hall 4: Charting the territory, The taking of Algiers

The French began drawing, exploring, mapping and representing the invaded territory as soon as they landed on the beaches of the peninsula of Sidi-Ferruch on 14 June 1830. This gave rise to numerous productions: views and plans of Algiers, maps of the city’s surroundings, sketches of the surfaces by the settlers of the Army of Africa. What the soldiers ignored was not surveyed and whatever was destroyed was simply erased from the surveys. The white contours of the maps suggest virgin spaces, limitless expanses.

Through its subjective power, the practice of cartography in Algeria participated, from its inauguration on Algerian soil, in the ideology of conquest. The army included in its ranks surveying engineers, invaluable draughtsmen and military artists. The model of the military and scientific expedition of Egypt (1798-1800) was still vivid. The motivations intersected from the first weeks of the occupation of Algiers and its suburbs: military conquest limited to “useful areas” and wholesale scientific knowledge went hand in hand during the first decades of the conquest.

Oil on canvas, Théodore Gudin, Attack on Algiers by Land and by Sea, 29 June 1830, 1831.

Gudin painted from the memories of the aggressors and summarized in a single image the two major events in the surrender of Algiers: the bombardment of the city by guns from French vessels positioned in the bay from July 1st; and the land invasion by infantry and artillery on 3 July to capture the fort, Sultan-Khalessi, the last rampart protecting the city. To the realism of the French uniforms, arms and tents, the painter added a setting essentially composed of plants and a few “Moorish villas”, already following the codes of Orientalist painting.

Hall 5: Charting the territory, Advancing into the territory

In France, artists and publishers took over from the military and popularised new images of Algeria. Meanwhile survey engineers on site in Algeria, under the protection of the cavalry, conducted surveys of the topography that served to establish the sheets of the map of Algeria with scales 1:200 000 and 1:400 000. Thus the highly precise representation of the territory was instantaneously born, although no schema of domination was determined or agreed upon.

To map, conquer, dominate, such were the motives of the officers of the French expeditionary forces, which evolved into the Army of Africa. The blank areas of the map disappeared with the reconnaissance and the surveys necessary for both the development of the map and the pursuit of the conquest. Three coastal areas were the first to be exploited. In the centre, Algiers and its surroundings. To the west, Oran and Mostaganem and to the east, Bougie and Constantine.

Hall 6: Charting the territory, Occupying the territory

Since the conquest, advocates of colonisation by Europeans settlers worked to develop centres of colonisation. The first Europeans settled in precarious camps. But it was not until 1842 that a planned settlement of “pacified” lands was established under the government of Louis-Philippe: a large-scale settlement of Europeans, mostly French citizens.

After the workers’ revolts during the revolution of 1848 and the advent of the Second Republic, the population displacement accelerated. Colonisation involved the transfer of land ownership, which the military governor general undertook according to three modalities: the sale of land incorporated into the public domain; the sequestration of properties belonging to individuals and families that resisted the occupation; and the purchase by expropriation from indigenous property holders.

Adrien Dauzats, The Iron Gates Pass, series of six watercolours and gouaches on paper, 1841:

Adrien Dauzats, painter attaché to the military expedition led by the Duke of Orléans (son of King Louis-Philippe) and the Maréchal Valée - who with the assistance of local informants established a land connection in October 1839 between Algiers and Constantine - produced six watercolours of the march known as the Iron Gates. Depicting the monumental stacks of carved limestone walls, superimposed rocks and steep slopes, he evokes the heroism of the soldiers of the 17th infantry regiment. The expedition, crossing the territory of the Bibans administered by Abd el-Kader, brought an end to the 1837 Treaty of Tafna reviving hostilities with the latter until their surrender in 1847.

Map of the areas surrounding Philippeville, lands proposed for an indigenous reserve, around 1840-1842:

After a decade of occupation, France decided to organise the colonisation of the territories by displacing the local populations and reserving the fertile lands for settlers brought from Europe. This process of “setting aside” the indigenous Algerians, on marginal lands, utterly devastated the way of life of these populations and their land-use practices.

3: Conquering Algeria – From excessive imagery to the end of French Algeria

Hall 7: Conquering Algeria, easy to control

Building a new society, in which Europeans would be the pillars, involved destroying and transforming: removing the existing structures, demolishing the original settlements, remodelling Ottoman Algiers and establishing a new port city. Once the capital was conquered, the French immediately transformed the urban fabric following the model of New World cities. Urbanism is inspired by the chessboard: right angles, large streets, squares, and cultural and religious public buildings.

The influx of settlers beginning in 1842 disrupted the way of life and agricultural economy of the indigenous peoples and transformed their landscapes. Algeria conquered; the central government created an administration in 1844 intended to supervise the local populations through what was inappropriately baptised the “Arab offices”. In 1848, Algeria was annexed to France and divided into three Départements: Oran, Algiers and Constantine.

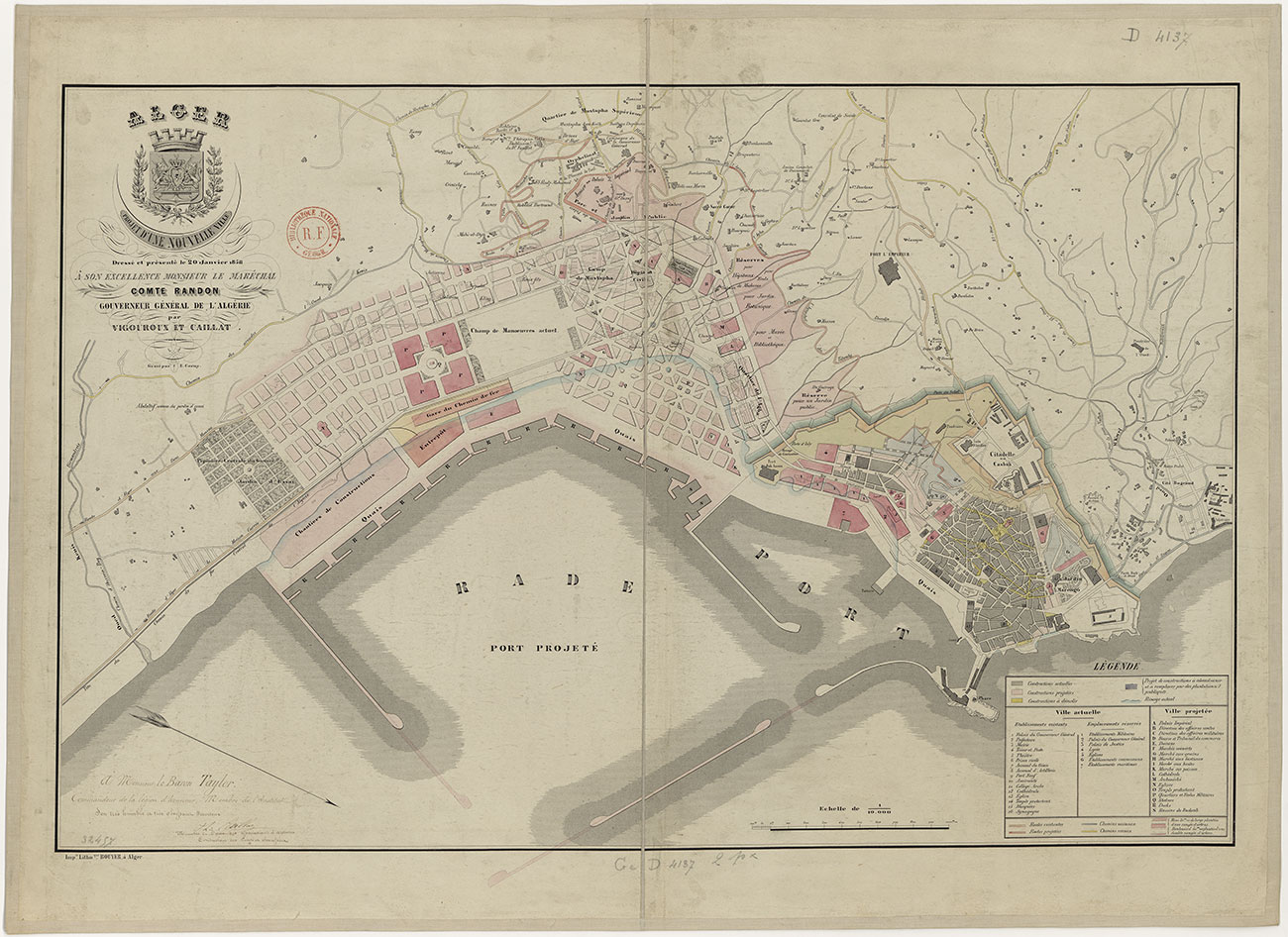

Vigouroux et Ph. Caillat, Alger. Projet d’une nouvelle ville dressé et présenté le 20 janvier 1858 à Son Excellence monsieur le maréchal Randon, Alger, 1858 :

The Algiers extension project perceived as a “new European city” juxtaposed to the old white Muslim city, dated from 20 January 1858 and relied on the railway line commissioned by the decree of 8 March 1857. Wide arteries created a checkerboard urban fabric, with public and religious buildings, new quays pushing back the shoreline and a second extension of the port, an organisation of space according to activities, a functional link between the axes of transport and economic activities, and green spaces were among the elements illustrating that this would be a modern city served by the most important port in North Africa.

Hall 8: Conquering Algeria, Science in the service of colonisation

Scientific analysis of the territory began with the report of the African Commission established in 1833, whose mission was to rectify the errors of the conquest. Founded in 1839, the commission of scientific exploration was heir to the Enlightenment and based on the model of Bonaparte’s expedition to Egypt. It aimed to address in an encyclopaedic manner “everything” making up the Algerian territory: knowledge of the topography, geography, soil, sub-soil, fauna, flora, peoples, languages, “religious brotherhoods”, former Roman presence, and former extent of Christianisation. The proponents of colonisation collected the results in a manner that supported only the Christian origins of Algeria. Thus proceeded the writing and appropriation of history, cartography and gridding of space. This so-called scholarly and meticulous knowledge of the territory went hand in hand with the devaluation of indigenous knowledge.

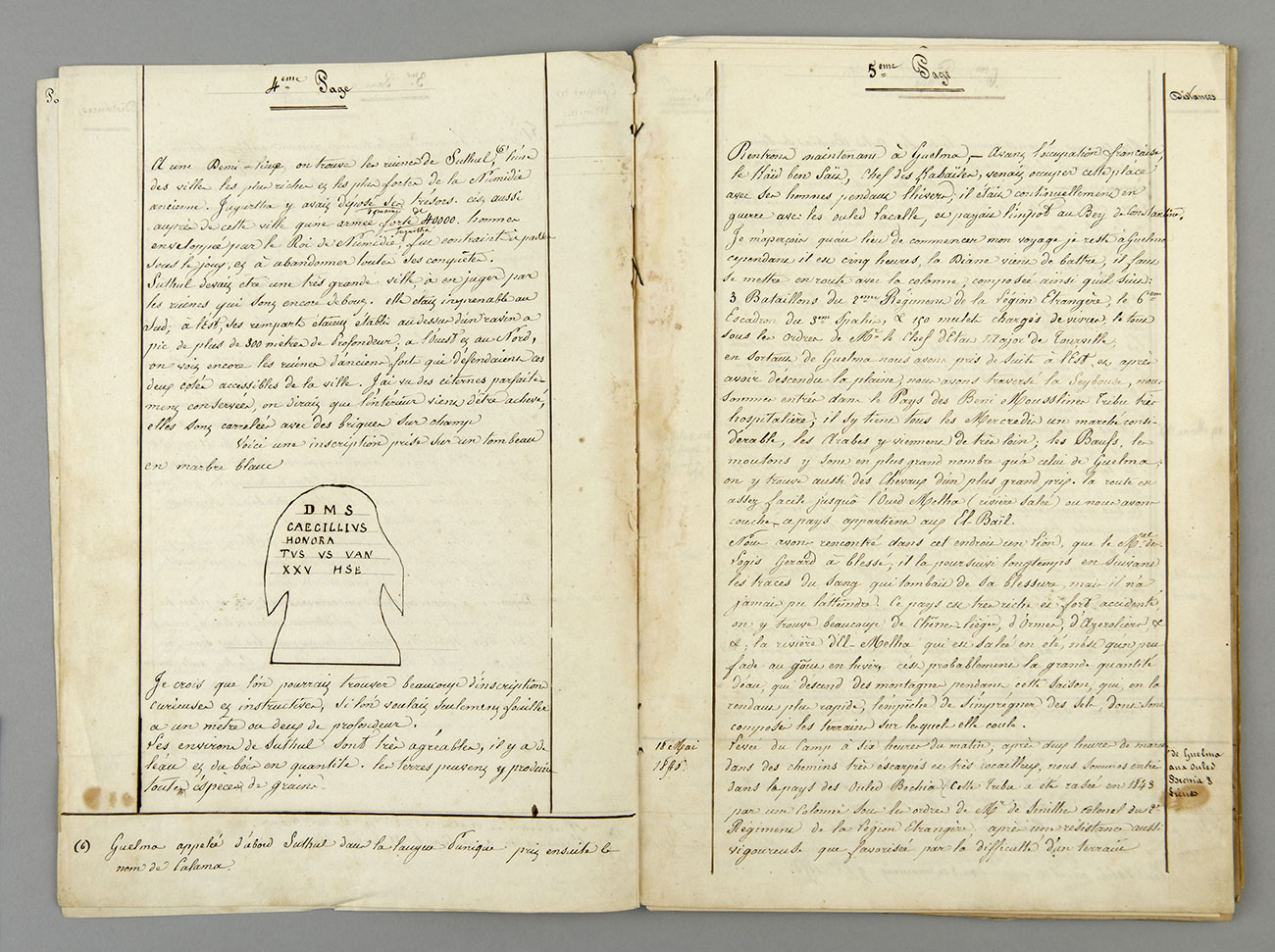

Carnet militaire. Voyage de Guelma à Tebessa, Jacques-Louis Randon,1846 :

The field notebook of General Randon was written in Batna in September 1850. It retraces the voyage that he took in May 1846 from Guelma, which he left after three years of residence, to Tebessa. It is full of sketches of archaeological ruins and epigraphic inscriptions observed from one site to another as well as beautiful portraits of the local inhabitants. He wrote that some of the Roman sites were in excellent condition and that they could be used to construct garrisons and the port.

Hall 9: Conquering Algeria, Crossing the Sahara

The more or less precise delineation of the conquered, colonised, and then governed territory was never a rational process and continued in the case of Algeria.

The border with the Regency of Fez (Morocco), gave rise in 1845 to a treaty in the form of a map containing the results of the boundary commission. This was not the case further east with the Regency of Tunis, even when the French protectorate was established in that territory in 1881. Similarly, the great Saharan territory was perceived as a boundless expanse on the principle of the American “frontier strip” from the westward expansion, a territory difficult to delineate. The southern populations continually pushed back the French military.

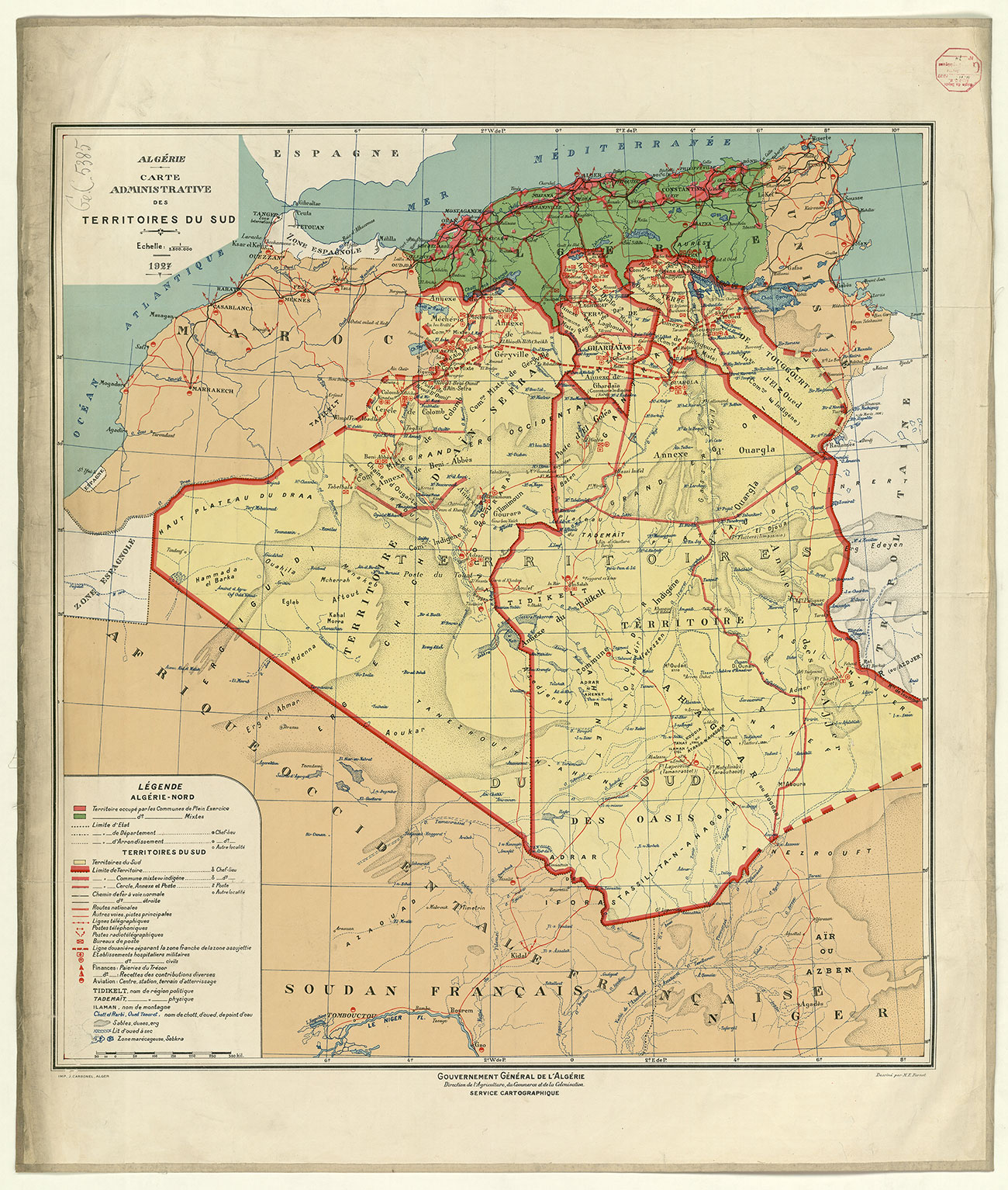

In 1899, a scientific mission facilitated the military takeover of In Salah. Located in the central Sahara, more than 1000 km from Algiers, this annexation opened the possibility of capturing desert areas and the exploration by the French administration of the southern Saharan territories as far as the Congo. The motorisation of traffic in the last third of the 19th century would accelerate (railway, trucks, planes…).

Hall 10: Conquering Algeria, the manufacturing of Algeria

Taking possession of Algeria occurred notably through the mapping of its space. While certain geographers were in favour of a respectful integration of the living conditions of the indigenous populations, others defended the maintenance of two statuses.

Populations called “Muslims” from Algeria did not enjoy the same civil rights as Europeans and were often relegated to agricultural work. Very early, geography served as propaganda for the French government. In 1842, the Algerian territory made its first appearance in a national atlas, serving the colonial imagery by bearing an unequivocal message: an agricultural land, radiant and timeless, and charged with Oriental stereotypes conducive to tourism.

In the interwar period the products coming from French Algeria as well as tourism contributed to the national wealth. Meanwhile the poverty of the local populations was increasing, and 75 % of the agricultural and manufacturing output was exported to Europe.

Hall 11: Conquering Algeria, the end of French Algeria

The media disseminated conveyed a schematic vision of Algerians that served trade and tourism. But these representations masked the reality of the indigenous populations’ lives. Even though they represented 90 % of the population, they were still excluded from the governance of the territory.

After World War II, the Algerians’ will to end colonialism would lead them to fight for their autonomy. In 1954 the Algerian war for liberation began. A long conflict ensued which would take the lives of thousands of women and men. This war ended with a referendum granting independence to Algeria on 5 July 1962.

During this entire period, France tried new social and economic policies, but they could not stop the movement of history, which was leading many countries toward independence, particularly in Africa. Thus began the long exodus of the so-called European populations of Algeria.

4 : Au plus près - Aperçus de l'Algérie après 1962

Hall 12: From up close

The independence of Algeria created an immense solidarity movement worldwide. The Algerian territory was maintained in its integrity, as delineated by the French authorities. The country experienced in the 1960s a rare political effervescence making Algiers the cultural capital of “third world” and Marxist movements from postcolonial revolutionary struggles. The major militant socialists of the era converged on this territory. Artists, filmmakers, architects and writers flocked from every continent.

From 1962 on, Algeria was committed to the path of reform. Major projects focusing on education, housing, health, agriculture and the development of infrastructure were realised. Socialism became the major political vector during this period. After various crises, the country’s economy tended toward liberalisation. According to the constitution, only Algerians had access to land ownership in Algeria.

Series of 14 colour photographs, Jason Oddy :

This series is part of a larger ensemble of photographs, produced by Jason Oddy, of the work of Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer, which he realised in Algeria during his exile in Europe (between 1969 and 1975). Shown here are images of the Université Bab Ezzouar and the Olympic Complex of Algiers, as well as the Université Mentouri in Constantine. With no human presence, the sites seem to be both slowly eaten away and frozen by time, while vernacular elements take over the surfaces and the original architecture gradually disappears.