The Splendours of Volubilis

Ancient Bronces from Marocco and The Mediterranean

|

From Wednesday 12 March 2014 to Monday 25 August 2014

Trough the exceptional loan of the ancient bronze collection from Morocco discovered at the archaeological site of Volubilis, the Mucem presents one of the key aspects of the ancient Mediterranean basin. Fruit on an accord signed between the Kingdom of Morocco and the French government, the exhibition reflects the close collaboration between the National Foundation of Museums of Morocco and the Mucem. This collection of bronzes from the Rabat Archaeological Museum is among the most outstanding of the ancient Mediterranean world. Although discovered for the most part at Volubilis, they were not produced in this region of the Roman Empire. However, they attest to a mode or modes in vogue in the Mediterranean between the 2nd century B.C. and the 2nd century A.D.

Nonetheless, we do not know their production sites, which could have been located in Italy, in Greece, as in the Oriental Mediterranean- Turkey, Jordan- or fabrication workshops discovered to date. Beyond their intrinsic technical quality, the bronzes from Volubilis are marked by an aesthetic particularly representative of the models present in the Greco-Roman Mediterranean. The ensemble of bronzes coming from Volubilis is staged facing works from other Mediterranean regions. Among these, we have benefited from the precious collections from the Louvre, the Cabinet des Monnaies, Médailles et Antiques of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, the Musée de l’Ephèbe d’Agde and the Musée Départemental Arles Antique. They illustrate brilliantly the common language of the Mediterranean elites of Antiquity. It is further testimony to this basin of civilisation which is the Mediterranean in the antique period: a vast open space where people have circulated since the first millennium B.C. from Tyr to Carthage, from Asia Minor to the Atlantic passing by the Black Sea, from Phocaea to Marseille, from Miletus to Olbia, from Thera to Cyrene…

General Commissioner: Myriame Morel-Deledalle

Scenography: Atelier Maciej Fiszer

Exhibition realised with the exceptional collaboration of the National Foundation of Museums of the Kingdom of Morocco, within the framework of a cultural cooperation agreement signed between Foundation and the Mucem.

Exhibition itinerary

Section 1: From Numidia to Mauretania Tingitana

During the reign of Juba II, the ancient kingdom of Mauretania, located in North Africa, was a huge territory on the shores of the Mediterranean, from the Atlantic Ocean to the east of present-day Algeria.In the east of this territory were the Roman provinces of Africa Nova and Africa Vetus, which were annexed by the Roman Empire during its wars with Carthage. Mauretania had been within the sphere of Roman influence since the 2nd century BC and was also subjected to the influence of the Greek world through the intermediary of Carthage.

In 25 BC, Octavian gave the Mauretanian kingdom to the young Numidian ruler Juba II, and then to his son Ptolemy, who was killed in Lyon on the orders of Emperor Caligula in 39 AD. In 41 BC, Mauretania was divided into two Roman provinces: Mauretania Caesariensis, with its capital Caesarea (modern Cherchell in Algeria), and Mauretania Tingitana in the west, whose capital was Tingis (Tangier in Morocco). After it was annexed to Rome, the region experienced a period of rapid, sustained growth that lasted right throughout the duration of the Roman occupation, to the end of the 3rd century AD. A rich agricultural province, Mauretania Tingitana fed the Empire, with olive oil and cereal production and salting factories, as well as the manufacture of rare furniture, all of which contributed to the province’s prosperity.

Families

Juba II, king of Mauretania from 25 BC to AD 23, was the son of Juba I. Captured and taken to the court at Rome after his father was defeated by Caesar, he was brought up by the sister of Octavius, the future Emperor Augustus, and received an excellent, comprehensive Greco-Roman education. In 19 BC he married Cleopatra Selene, daughter of Mark Antony and the famous Cleopatra VII. Like Juba II, Cleopatra Selene had been brought up at the imperial court from 29 BC, following the death of her parents.

In 25 BC, Octavian installed Juba II as king of Mauretania to pacify the country and develop the territory economically for the benefit of the Roman Empire. This was the paradox surrounding these two children, who were enemies of Rome but became its loyal ambassadors. Juba II, of African birth and Roman education, married to a princess with a Hellenistic culture, was an erudite king imbued with Mediterranean culture. According to the ancient authors, he was one of the greatest scholars of his time. By commissioning numerous works of art from artists throughout the Empire, Juba II developed a refined culture, influenced by Hellenistic and Egyptian currents. The ruler’s capital, situated at Iol, which became Caeresea, was thus a crucible for indigenous, Punic, Greek and Roman cultures, and where something of the spirit of Alexandria certainly still persisted.

The city of Volubilis

Located in Morocco, Volubilis was a site that had been occupied since the Neolithic period. The city reached its maximum size and greatest growth during the Roman period. Volubilis covered a total area of 42 hectares. The many olive oil presses testify to large-scale production of olive oil, which certainly contributed greatly to the wealth of the city and its growth. Under the impetus of the Empire’s administrators, the city was adorned with numerous bronze and marble statues. The settlers and merchants lived in huge, lavishly decorated houses, with reception rooms adorned with sumptuous mosaics.

Following the withdrawal of the Roman administration in 285 BC, the city was gradually abandoned. The site was identified in the 19th century and archaeological excavations started in the early 20th century. To date, half of the site has been uncovered. Over a period of several decades, various bronze sculptures were discovered. They were found scattered across various parts of the city, most of them buried in earth. The quality of these finds and the site itself prompted UNESCO to list Volubilis as a World Heritage site.

Section 2: Tastes and models

During the Roman Empire, between the 6th to 4th centuries BC, Greek models in the fields of pottery and marble and bronze statuary formed artistic touchstones that circulated from one part of the Mediterranean to another. The circulation of works, boosted by trade and pillaging in conquered provinces, was accompanied by the movements of people and skills.

The artists, usually Greek, worked throughout the Mediterranean basin, contributing to the spread of models. The Volubilis bronzes and the other works presented here reflect the different styles of Greco-Roman statuary.

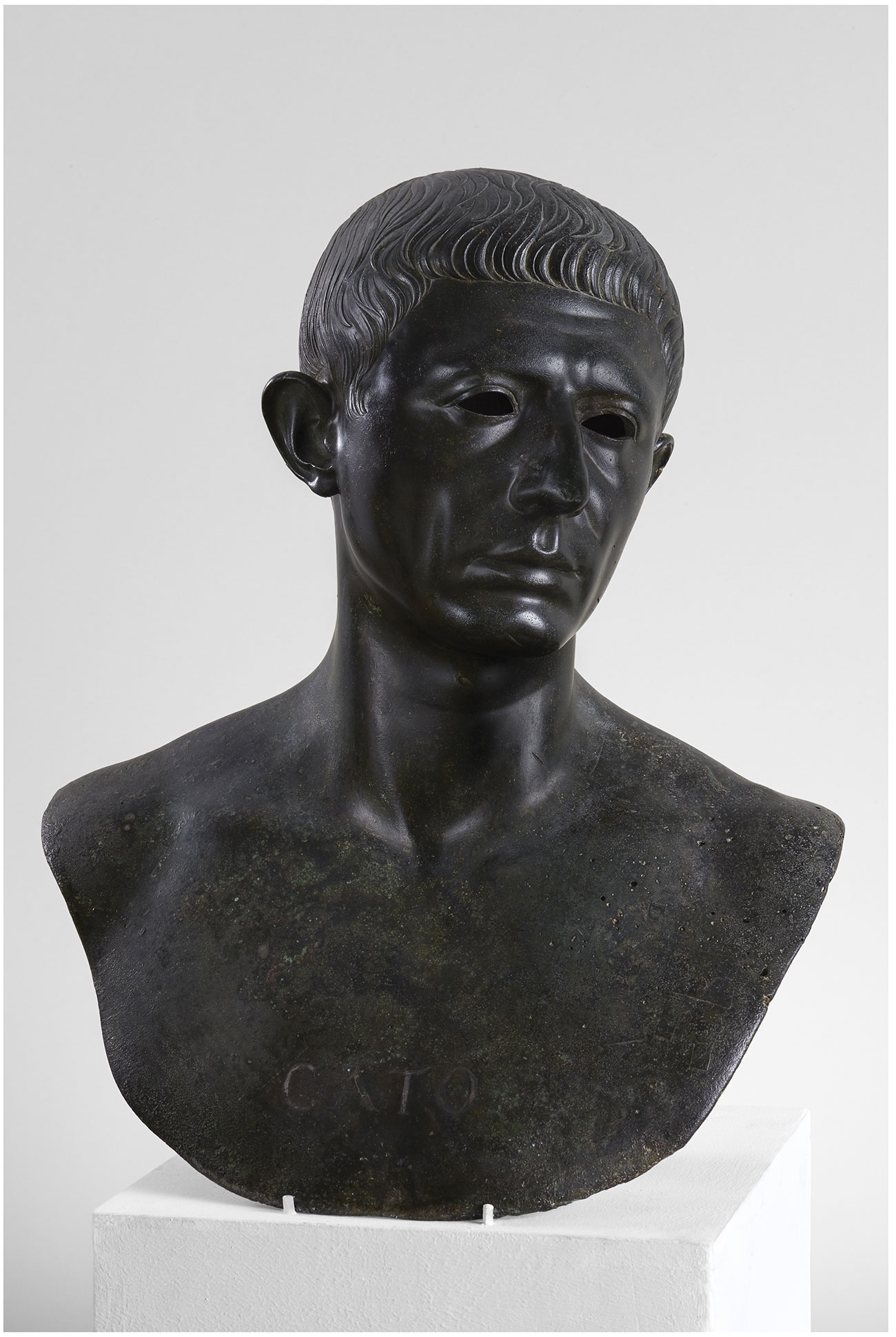

The political portrait

The political portrait, exemplified by numerous busts of emperors, was doubtless the most standardised type. Intended to disseminate the emperor’s image throughout the Empire, it conformed to precise rules laid down by the ruler, ensuring that facial features and expressions were recognizable from one statue to the next. During the period of Augustus, several artistic trends came to the fore in portraiture: the Greek tradition of the idealized portrait went hand in hand with the more realistic Roman portrait, with the aim of conveying the moral qualities of the citizen and the magistrate.

Thus the bust of Cato can be correlated with the bronze bust of Juba II. The latter depicts Caesar’s famous adversary, who was defeated at the battle of Thapsus in 46 BC, with a severe, haughty expression, close to the image of him presented in ancient texts.

Idealism

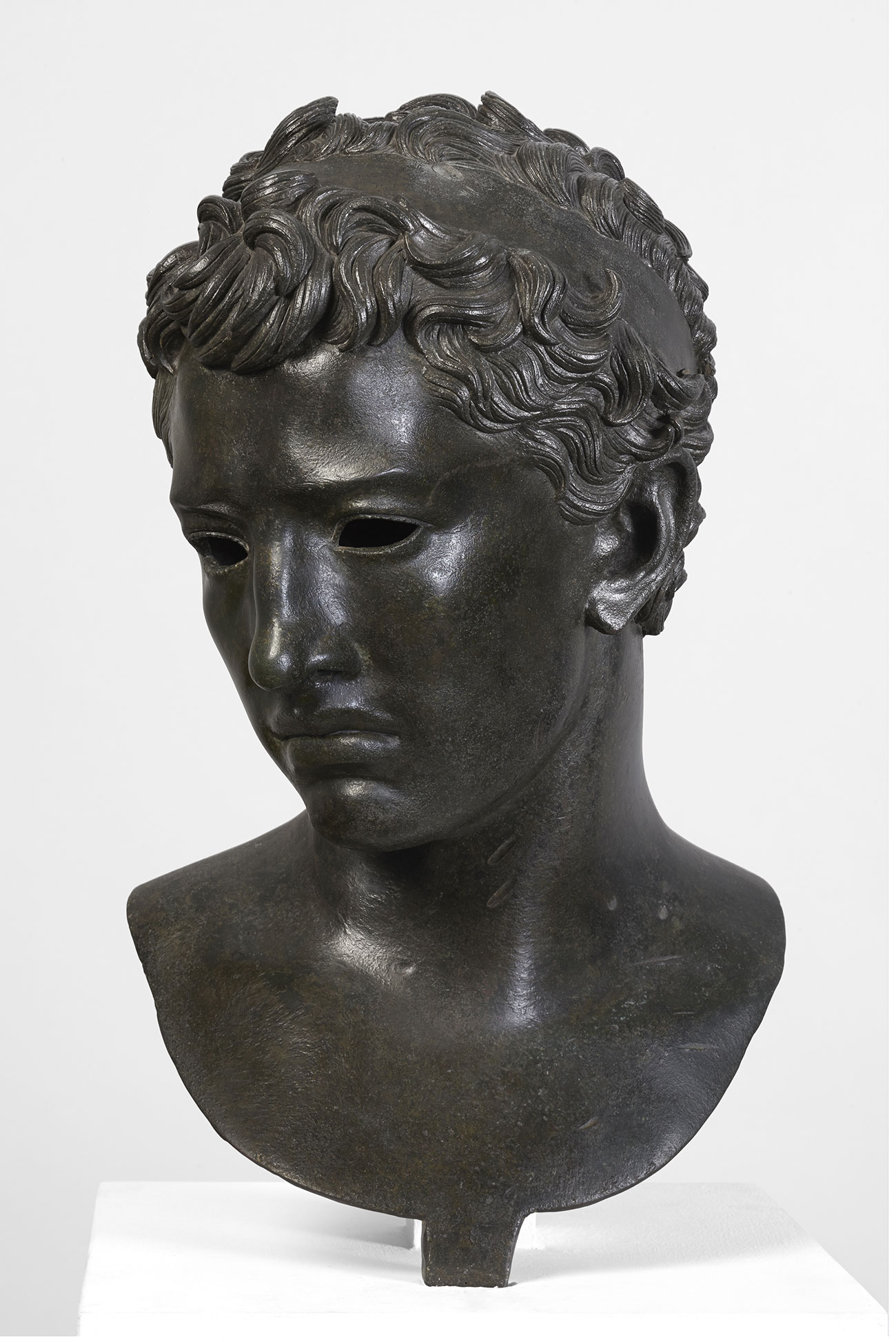

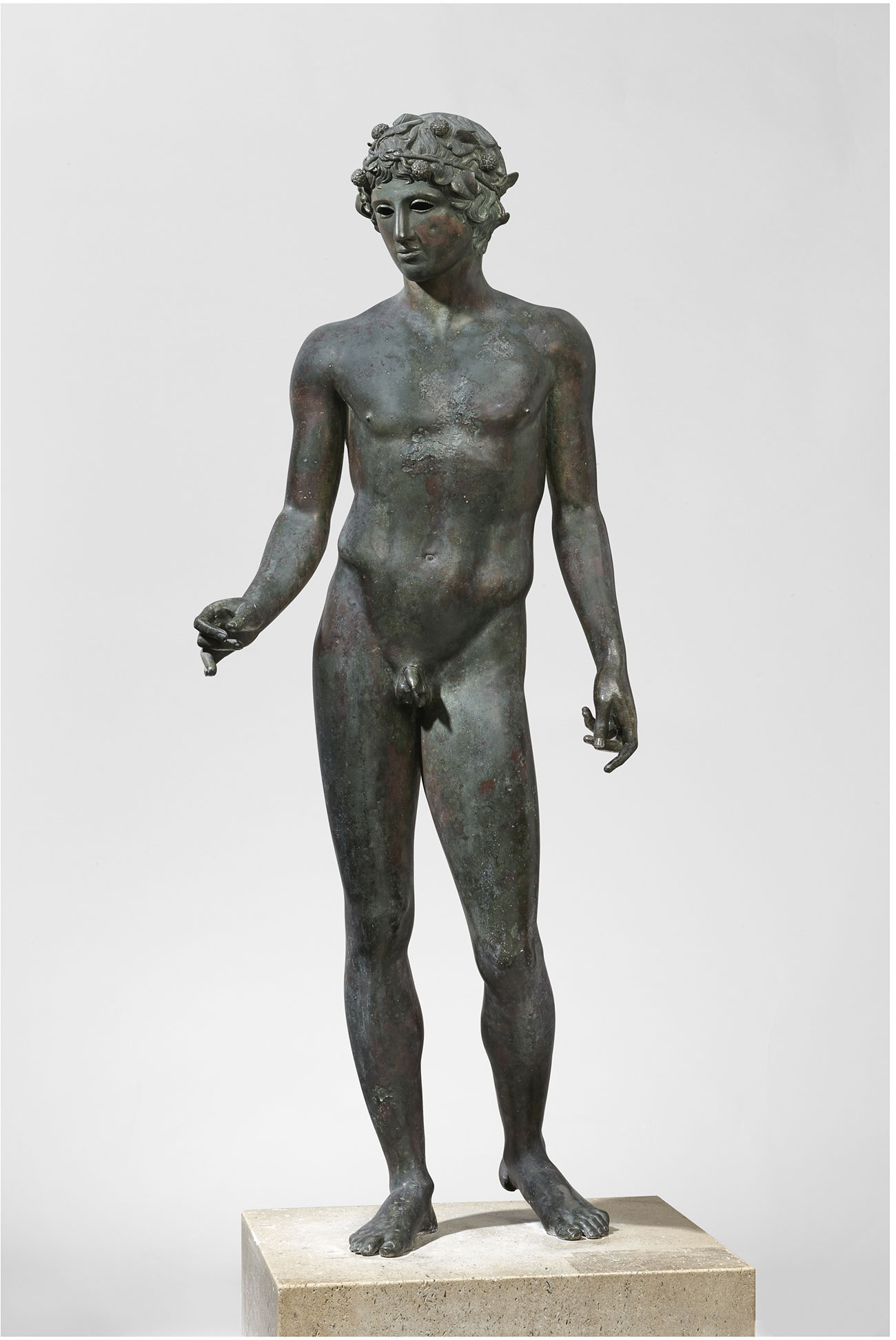

The prestige of Greek statuary and the circulation of works led erudite Romans to draw up catalogues of masterpieces by the most famous artists from the past. Greek sculptors who worked for wealthy Hellenistic and Roman clients thus drew inspiration from works by the great classical artists of the 5th and 4th centuries BC, whose nameshave been preserved by history: Polykleitos, Phidias and Praxiteles. The influence of this ‘classical’ style can be seen in the ephebes of Volubilis and the bust of the athlete known as the Benevento Head.

The Rider and the Horse hark back to an older artistic period, known as the Archaic period (6th–5th centuries BC). From the end of the 1st century BC, artists imitated this more severe style, while seeking to reduce its stiffness.

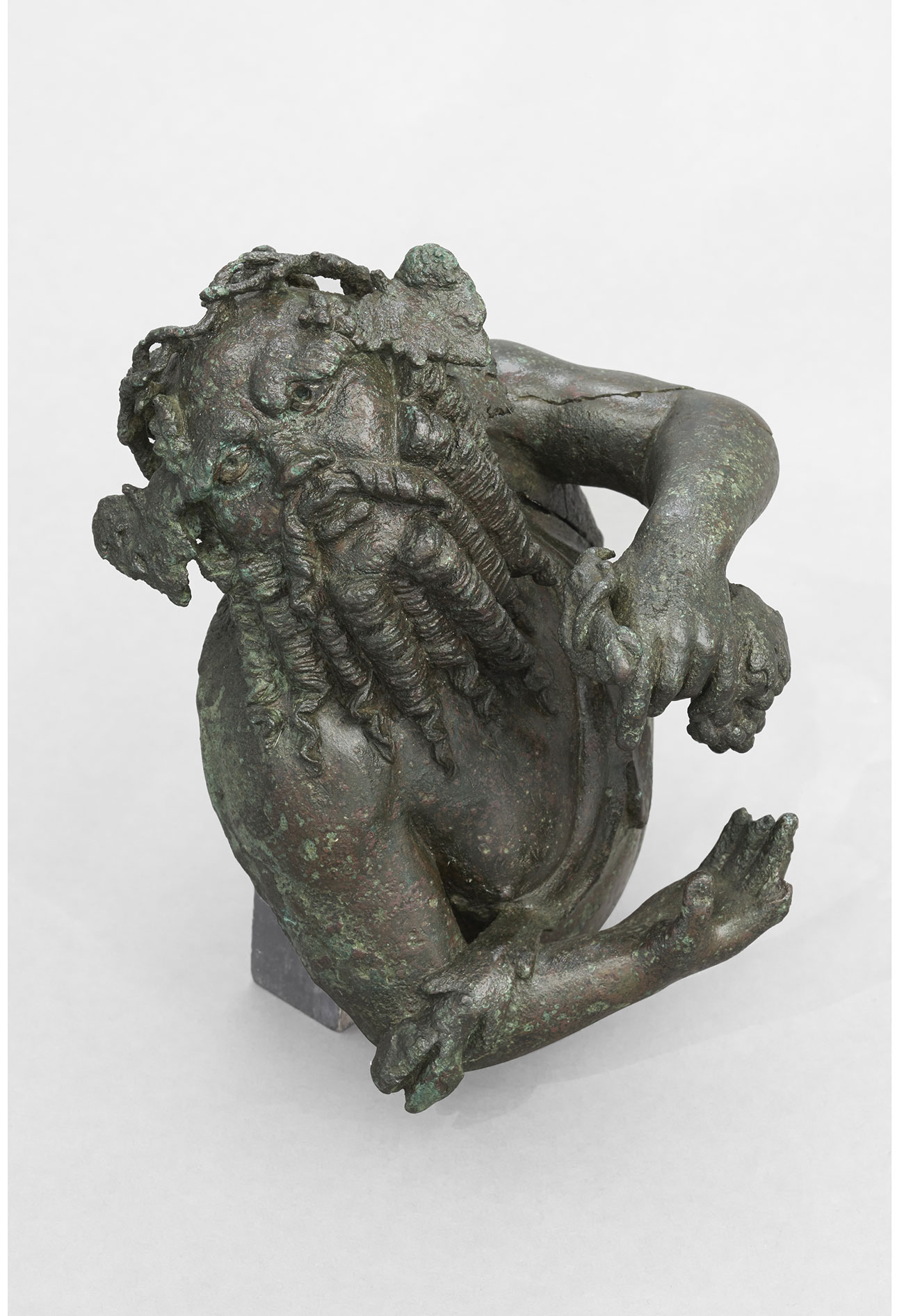

Domestic decoration

The different styles of Hellenistic sculpture that were imitated during the imperial and Roman period include the so-called “grotesque” or ”genre” style, which was based on models that probably originated in Alexandria. This type of sculpture sometimes went hand in hand with mythological decorative elements, in marble or bronze, used to adorn gardens and fountains, bearing witness to the refinement of Roman homes: the world of childhood and that of Dionysus, and evocations of the pleasures of hunting were all metaphors for the joy of living. Genre sculpture, illustrated here by the Old Fisherman, depicts ordinary people such as peasants, shepherds, and fishermen.

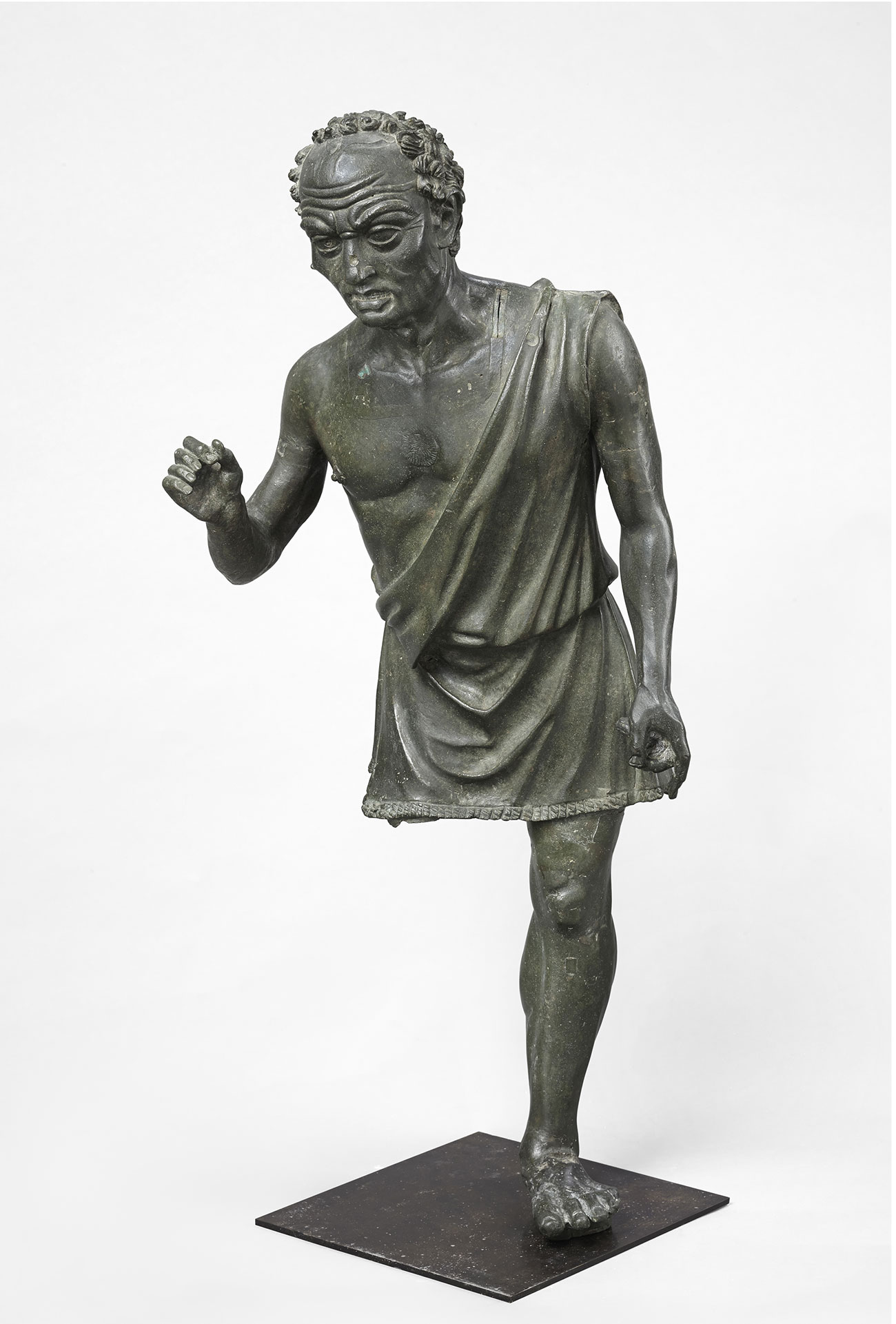

Depicted in the process of performing rituals or making offerings or sacrifices, they embody a rustic form of piety that is both fervent and sincere. Other types of representation accentuate the “naturalistic” traits to a grotesque degree, for example by caricaturing the features of exotic people (balsamarium in the form of the head of an Egyptian) or the comical poses of performers (the dancer from Arles).

Decoration in the home (furniture, tableware) was also made up motifs from a standard repertoire, including animals, mythological creatures, cupids and Eros. The remarkably realistic Dog about to jump shows the skill of the bronze-workers at producing animals. Found in the baths in the north of the city, this dog is no doubt served the spout from a fountain

Section 3: Bronze techniques

The existence of metal-working workshops in Mauretania Tingitana is attested, but no workshop has been found in Volubilis. Traces of workshops and tools are few and far between and difficult to identify, for workshops were temporary and itinerant. It is thought that the bronzes found at Volubilis were not made there, but were imported, probably from Greece or Italy.

The discovery in Rabat, unlinked to any archaeological context, of several male heads in plaster that are related to workshop models suggest that Mauretanian bronzeworkers were able to produce works of art. Although there were some itinerant bronze workshops, it is likely that most of the bronzes discovered in Volubilis were imported; it is thought that they were bought in Greece or in Italy, or that they were pillaged or came from the trade in pillaged spoils. Most of the large bronzes were hollow cast in foundries using the direct lost-wax method.

The techniques and different stages in the making of bronze, as well as the tools used, have changed little since antiquity. Several displays will help you to understand and follow the creation of a sculpture in a bronze workshop.

Virtuosity

The bronze statues of antiquity display exceptional mastery. Bronze is an alloy composed of copper and tin, to which lead was sometimes also added. During antiquity, works in polychrome bronze were produced, with a colour that was close to gold, but yellowish or pinkish in hue according to the amount of tin in the alloy. Importance was attached to the sparkle and lustre of the metallic surface. This polychromy was achieved by the addition of copper and silver. Copper was used to tint certain parts of the body, such as the lips (like those of the Benevento Head), to depict the blood of a wound, or specific parts of clothing.

The addition of silver was reserved for the teeth, the eyes and drapery elements. Today, the bronzes have lost their original colour and have darkened. At the time, attempts were no doubt made to delay this natural process of corrosion, for example by coating the statues in oil or bitumen. This phenomenon is thought to have gradually led to a change in taste, no doubt evident in the use of dark artificial patinas: the black patina made with sulphur and the famous black Corinthian bronze.