I love panoramas

|

From Wednesday 4 November 2015 to Monday 29 February 2016

From mountain ranges to Mediterranean coasts, certain places offer their visitors privileged points of view, which can provoke the feeling of dominating the world, possessing it, even dissolving it.

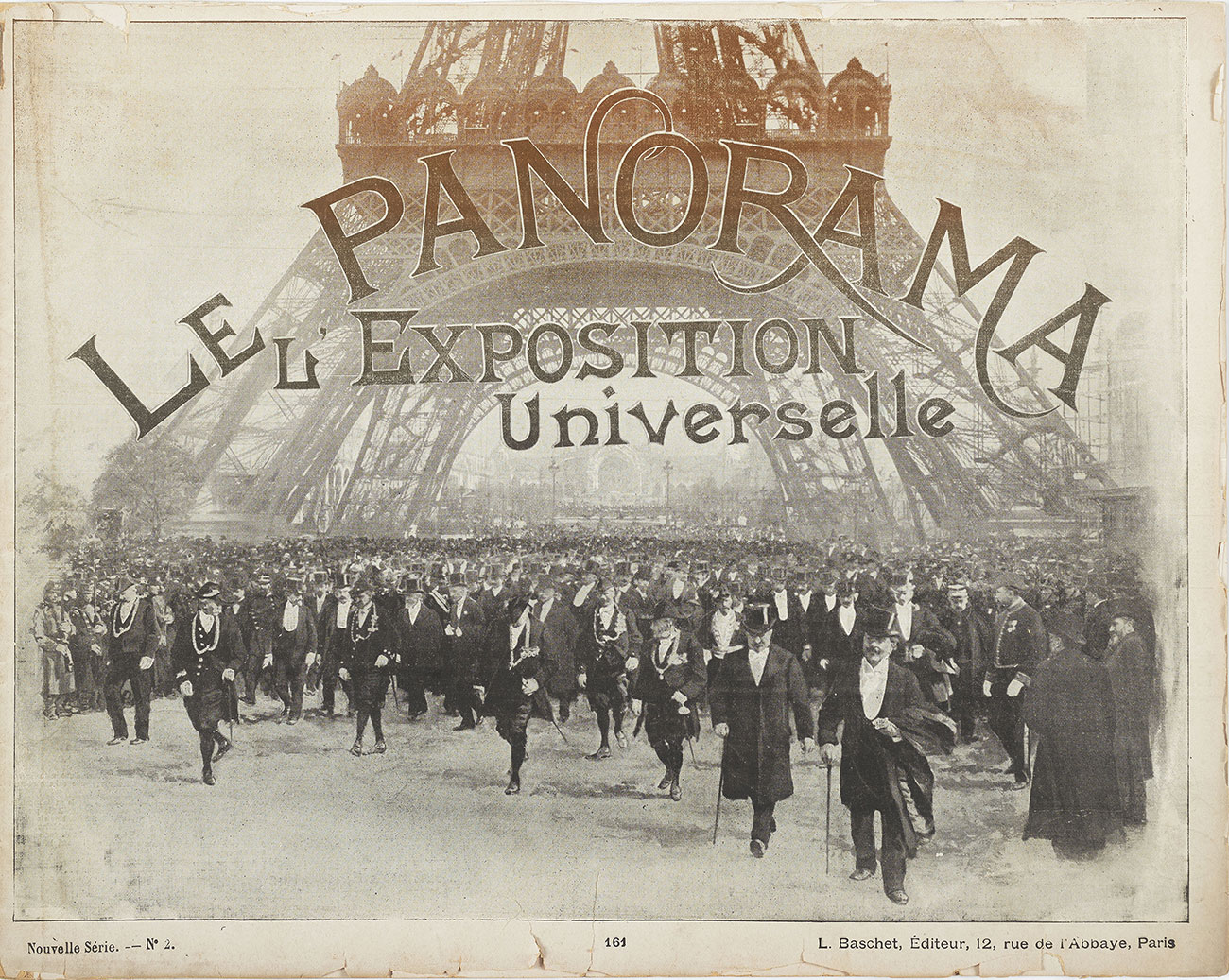

The word “panorama” was first used in England in 1787. It referred to a circular structure that placed spectators in the centre, where they could discover a landscape or a historical scene. Reproduced in an illusionary manner, it unfolded 360° around them. The term later resurfaced in France, in 1830, where it was simply an expression for sweeping landscapes, or expansive views. Later, its meaning rebounded encompassing both the succession of images perceived by the mind as a complete vision and the almost exhaustive study of a subject…

These different meanings convey the very essence of the panoramic phenomenon: the central role of perspective, a certain appropriation of the world that follows, the feeling of dominating a situation simply due to having a wide and complete view... by creating an illusion of reality that even competes with it. Indeed, the different forms of panoramas pose the question of the construction of perspective.

The exhibition I Love Panoramas, fruit of a close collaboration between the Musées d’Art et d’Histoire de Genève, Geneva and the Mucem in Marseille, seeks to demonstrate how the notion of the panorama surpasses typical categories of representation (fine arts, contemporary art, photography, cinema, industry, amateur practices…). Stemming from scientific and military logic prior to being appropriated by the society of the spectacle, the panoramic experience poses the question of our relationship to the world or to the landscape, mastered or unknown, to mass tourism, to the consumption of formatted points of view, as a source of entertainment.

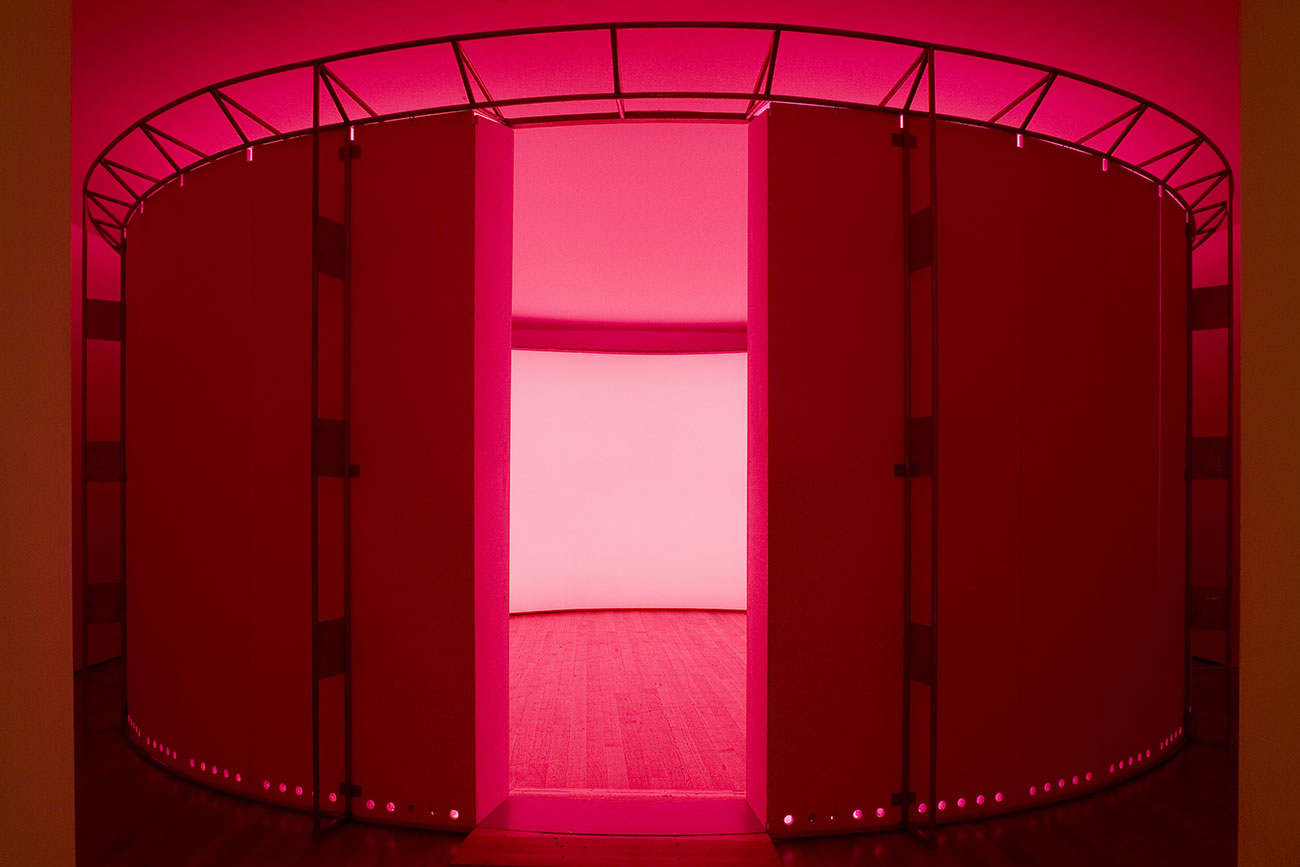

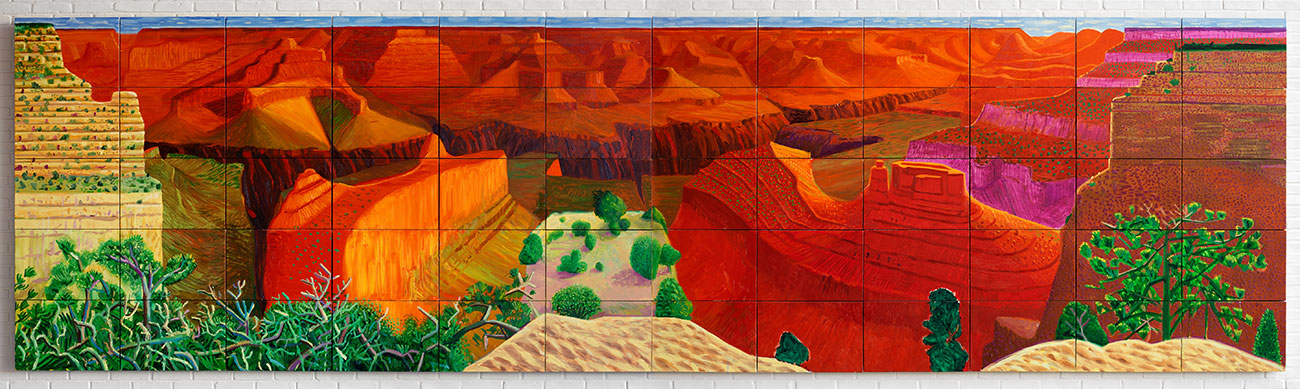

From the first drawing of a panorama filed by the American inventor Robert Fulton at the Institut National de la Propriété Intellectuelle in Paris, in 1799, to 360° room for all colours, by the Danish artist Olafur Eliasson, created in 2002, this exhibition offers a wide chronological range. In bringing together works by artists such as Jeff Wall, Peter Greenaway, David Hockney, Vincent Van Gogh, Gustave Courbet, Gerhard Richter, Jan Dibbets, François Morellet, and Ellsworth Kelly, it highlights the diversity of the artistic proposals influenced or marked by the notion of the panorama.

From photographic surveys of the Alps to those of battlefields by way of wallpapers, postcards and films, records, mediums and worlds mix and renew the way we look at the world and the role of the viewer.

Temporary exhibition, organised jointly by the Mucem and the Musées d’Art et d’Histoire, Geneva.

Commissariat : Jean-Roch Bouiller, Chief Curator, Head of Contemporary Art at the Mucem, and Laurence Madeline, Chief Curator, Head of Fine Arts at the Musées d’Art et d’Histoire, Geneva

Scenography: Adrien Rovero Studio

Graphic art: Camille Sauthier, Atelier Valenthier

Exhibition itinerary

Birth of an exhibition

This exhibition is the result of a misunderstanding surrounding the line “I love panoramas”, delivered by Jean Dujardin in the film by Michel Hazanavicius, OSS 117:Cairo, Nest of Spies. These three words immediately and serendipitously crystallised the main axes of reflection about the concept of the panorama. This phrase appears on one hand to be a commonplace statement that anyone could make before any landscape, evoking contemplation, nonchalance and pleasure. On the other hand, the fact that this comment is delivered before the Suez Canal in 1955, one year before its nationalisation and the ensuing conflicts, demonstrates the potential geopolitical dimension of any enterprise intended to offer an encompassing vision of reality. Panoramas are sources of contemplation, certainly, but also of appropriation, domination, even alienation.

The richness and paradoxical nature of the subject have emerged at the same time that the value of a partnership between a museum of art and history and a museum of civilisations has become evident. Each brings its own understanding of knowledge, of the subject, of the works. Their perspectives from cities like Geneva, open to alpine vistas, and Marseille, whose geomorphology offers numerous maritime viewpoints. As the project unfolded, it was amusing to discover that the 100th of the hundred stairs designed by Peter Greenaway for his operation Stairs 1, in Geneva in 1994, was to have been installed near the mouth of the Rhône, in Marseille or nearby.

Jean-Roch Bouiller, Chief Curator, Head of Contemporary Art at the Mucem

Laurence Madeline, Chief Curator, Head of Fine Arts at the Musées d’Art et d’Histoire, Geneva

1: The panoramic device

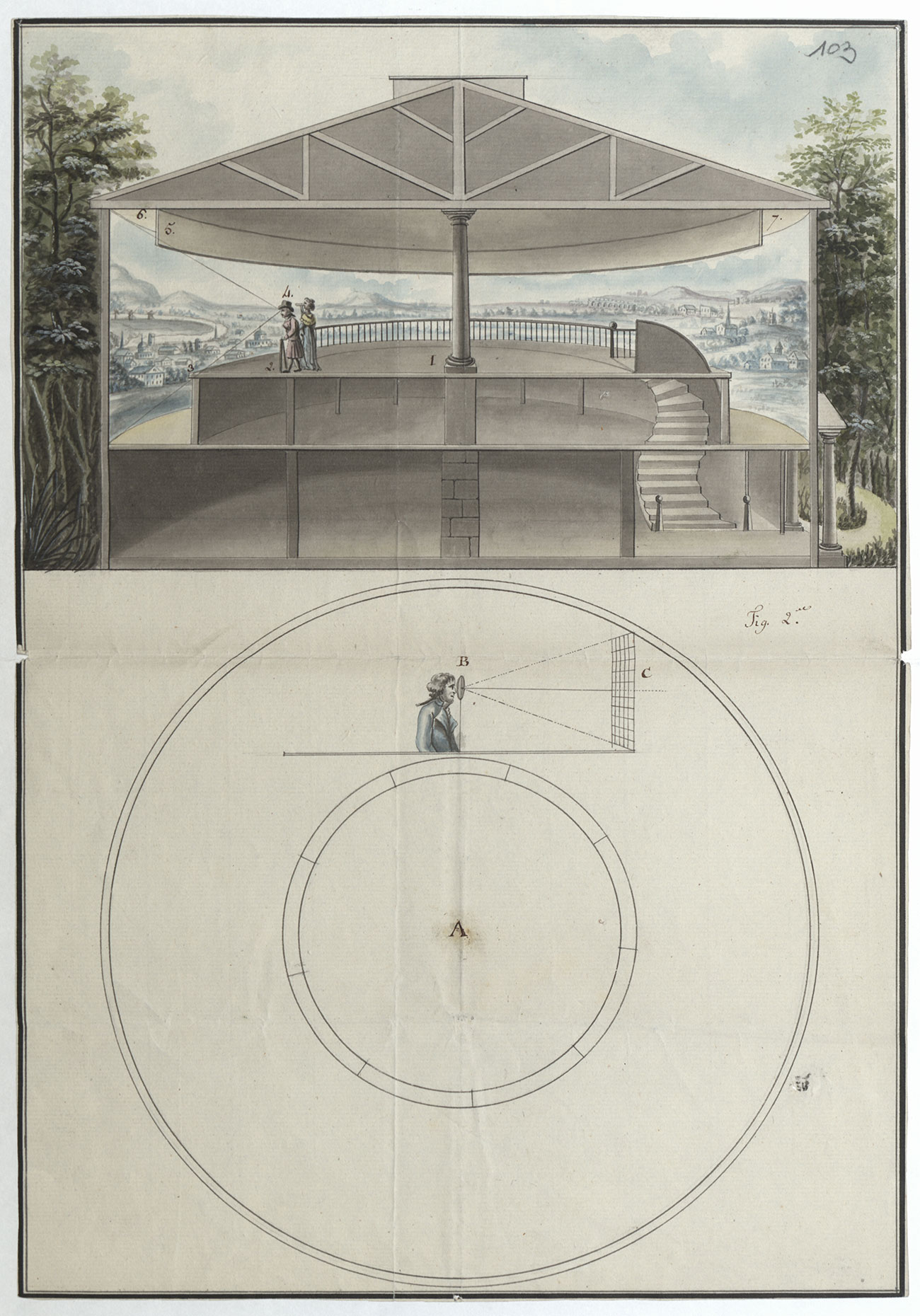

The panorama was originally a circular construction (rotunda) displaying a landscape or a historical scene, in specific conditions (central platform, zenithal lighting, darkened corridor, continuity of the motif presented) and usually charging an admission fee.

This device was invented by the Scottish painter Robert Barker in 1787 and quickly spread with the sale of patents filed in different European capitals. The first panoramas developed were devoted to views of cities (Edinburg, London, Paris…) and were rapidly accompanied by battle scenes.

This section gathers the plans of panoramic constructions (the patent filed by Robert Fulton at INPI to develop Robert Barker’s invention in Paris; Louis Bonnier, Avant-projet pour le pavillon des Nymphéas); paintings serving as drafts for the realisation of monumental panoramas (Jean-Pierre Prévost, Panorama de Constantinople); fragments of dismantled panoramas (Henri Gervex and Alfred Stevens, the Panorama du Siècle, certain pieces of which were cut from large panoramic canvases and transformed into easel paintings); and posters documenting the entertainment industry to which panoramas certainly belonged. It closes with the work of Jeff Wall, Restoration, which places in tension several concepts particular to the panorama: architecture or the format of a painting? A representation of reality or an illusion?

About Jeff Wall

Jeff Wall’s photographs consist of sophisticated stagings. Appearing to be scenes from daily life taken spontaneously, they in fact feature actors meticulously directed by the photographer. To have placed conservators in the Panorama Bourbaki, six years before its actual restoration, highlights the ambivalence of notions of reality, illusion and fiction inherent in the very principle of the panorama. By revealing behind the scenes, the luminous device of the glass roof is a mise en abîme in this game of illusion.

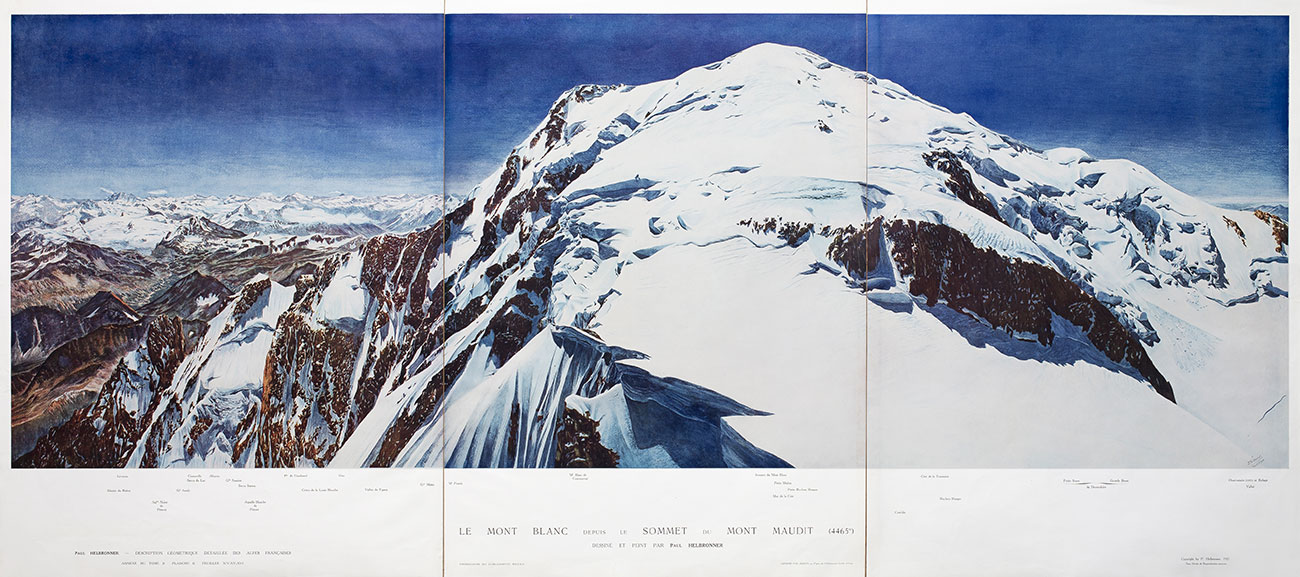

2 : The panorama as survey

The panorama also reflects a scientific approach to the world. It is not insignificant that the circular representation of a landscape was invented almost simultaneously in Switzerland, by the scientist Horace-Bénédict de Saussure in 1776, and in Scotland by the painter Robert Barker in 1787. These inventors’ approaches are justified and complemented by this common desire to identify a universe in its entirety. For the former, it was the Alps, hitherto largely unattainable. For the latter, the city of Edinburgh, more easily accessible but in full industrial transformation and thus difficult, as a result, to grasp as a whole.

This second part of the exhibition demonstrates that panoramic vision is vital to different types of representations of reality: the geographic survey (mountain chains, the Grand Canyon, contemporary geographers), the urban survey (panoramas of Marseille, from 1729 to the present, of Istanbul, of Nagasaki...), the military survey (of conquered territories or those to be conquered, of battlefields) or even surveys of unknown worlds (William Hodges, companion on the expeditions of Thomas Cook; assemblages of images of the moon by NASA teams). The works of Jean-Charles Langlois and Jean-Baptiste Durand-Brager, commemorating the victories of the French army, recall that the panorama is potentially a type of propaganda. Those of contemporary artists Julien Audebert, Renaud-Auguste Dormeuil and Alexis Cordesse highlight its political dimensions.

About Renaud Auguste-Dormeuil

The photos from the series Hôtels des transmissions - jusqu'à un certain point are panoramas of cities reclaiming the graphic vocabulary of the orientation table. But rather than tourist information, here the artist indicates all the places of power, official buildings, military or industrial infrastructure that could be potential targets of bombings or attacks. The hotel offering tourists the best views of the city insidiously becomes an ideal observation post for other uses.

3 : The construction of perspective

There are not just panoramas with precise determinations for viewer placement, which define a point of view in reality. There also exists a whole set of promontories, gazebos, terraces, stairs, balconies, benches and even optical instruments that guide the gaze physically and concretely. The works of Johan Christian Dahl, Peter Greenaway and Juan Muñoz, presented in this exhibition highlight this effect. Yet there are other ways to draw the eye, in a more suggestive or ideological manner, for example, through the indication of particular points of view, like highway signs, used as supports for paintings by Bertrand Lavier or the pictograms of gazebos collected from around the world by Jean-Daniel Berclaz. Halfway between the physical and ideological orientation of the perspective, the Point de vue portatif, by Philippe Ramette, emphasises this paradox. It is the irony of wanting to promote a free, open, infinite view, which ends up by being directed.

About Bertrand Lavier

In appropriating the road signs on motorways that indicate nearby tourist sites to drivers, Bertrand Lavier intended to re-discover historical or geographic sites that had lost their meaning, thereby restoring power to the regard.

4 : The panorama as narrative

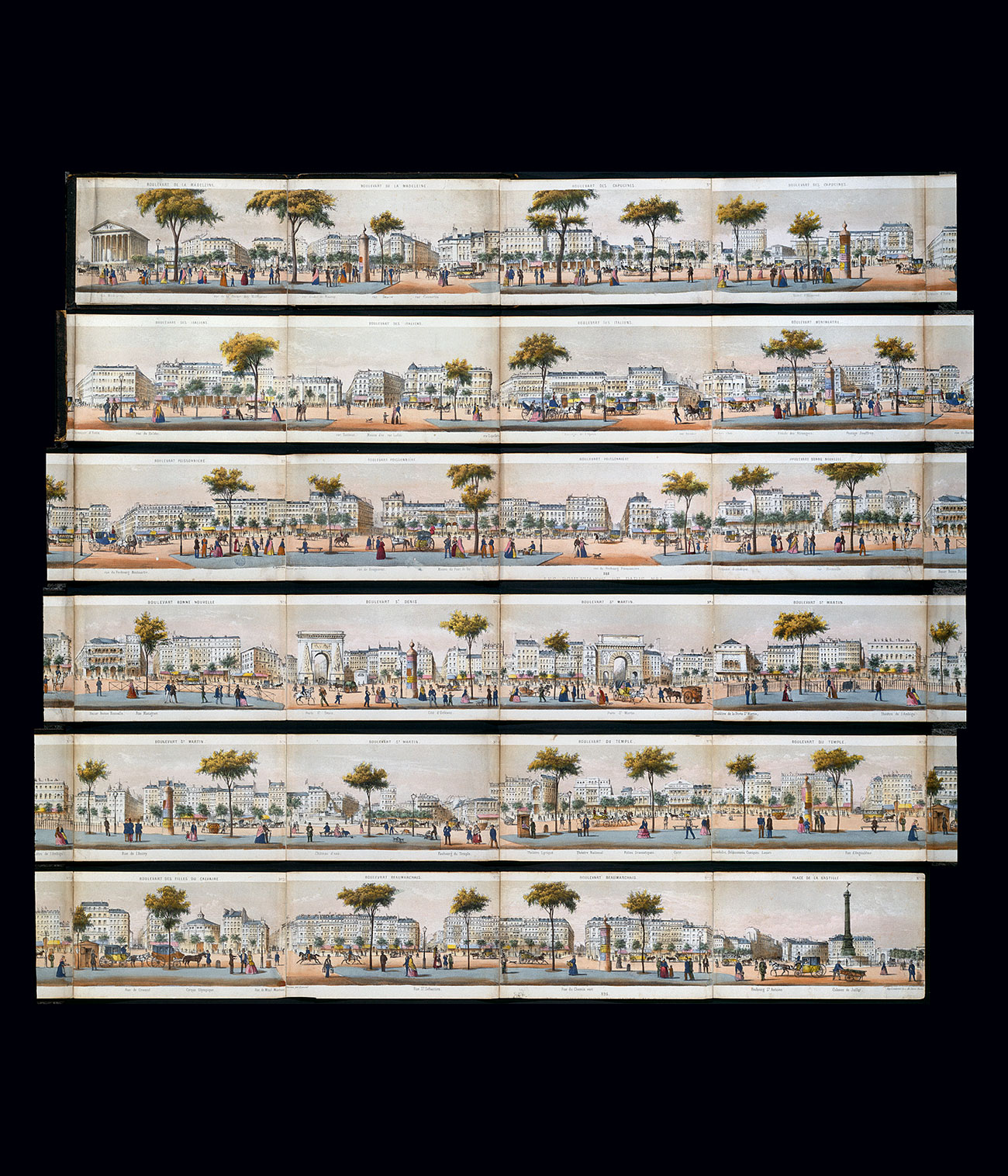

The Tapisserie de Bayeux was considered by historians as a potential precursor of the panorama from the 18th century. Indeed, the way of reporting events on a pictorial frieze, narrative, even idealised, or gathering, in a single image, an entire social group, resembles panoramic vision. The design of panoramic photographic cameras since 1845, the diffusion of accordion folded books called leporellos, have encouraged many enterprises aiming to fit into a single image various kinds of abstracts of the world, the narrative threads underlying representations of society or a part of society. Such a social group, such an association, such a family: wanting to see themselves in the form of a collective portrait. There each finds themselves in the place that they were assigned. The panorama has this ability to concentrate, in a single image, a vision of the world and to induce a narrative, which can be found in Asian parchment as in films at the cinema.

About coloramas

The Colorama was more than a panorama. It was a publicity stunt designed by Kodak that was on view at Grand Central Station in New York, from 1950 to 1989. On a surface of 100 m2, with a length of 18 m, an enormous image backlit by 1 km of tubes produced a visual spectacle every three weeks, staged by photographers, including Peter Gales. In this railway station, New York commuters contemplated 565 panoramas over forty years: inciting the purchase of cameras certainly, but above all veneration for the “true image”, the perfect image. (According to François Cheval.)

5 : The panorama as substitute

The taste for the contemplation of vast expanses does not end when viewers no longer have access to these views so sought after by travellers. The panoramic format also constitutes a way of replacing these privileged geographical areas that provoke the sensation of dominating the world. From the 18th century to the present, the installation of panoramic wallpaper in homes could thus be interpreted as a way of displaying power. Many other objects were created to serve as supports for the memories generated by the contemplation of real panoramas. Vedute, postcards, brochures, pens… evidence of an object economy that captures mass tourism and enables the sharing of a lived panoramic experience or the diverting of it for personal use. These small tangible panoramas crystallise the dreams, fantasies and desires for escape.

About Jean-Gabriel Charvet

Appearing at the end of the 17th century, the production of papier peint or hand-printed wallpaper developed after 1750 and experienced a century of apotheosis after 1800. Created in 1804 in Mâcon, by Joseph Dufour, Les Sauvages de la mer Pacifique is a testament to this expertise and this fashion. An illusionary device it encouraged dreaming of a “mythologised elsewhere”, giving the sensation of expansiveness to enclosed spaces while flaunting the control over territories considered until then as savage. The Zuber factory continues today to produce panoramic papiers peints.

6 : Man facing a monumental landscape

The invention of the panorama by Robert Barker in 1787 was both praised and criticised by the artists of his time. It radically challenged the laws of painting, conceived of since Alberti and the Renaissance as an imaginary window, materialised by a frame. Yet, if the frame disappears, the image can extend without limit in optimal lighting and visual conditions. The painting of history and especially the painting of landscapes were indeed confronted by new expectations regarding perspective. This revolution coincided with the Romantic period, which perceived the world in its most extreme dimensions, particularly through the question of the sublime, the most poetic and the most mystical. Before the landscapes offered to him, man is either placed in the position of dominating or being dominated. He can embrace the universe within his grasp, or dissolve it, merging with the infinitely large or the infinitely small, immensity perfectly recreated through panoramic formats, approaching geometric or coloured abstraction. It is this dual feeling of domination and submission that reflects the paintings gathered in this section.

About David Hockney

The work of David Hockney represents a type of summary of the exhibition: the reference to the scientific survey of the Grand Canyon conducted by Holmes in the mid-19th century, the reflection on the point of view, the position of the viewer between feelings of domination and of dissolving into the great landscape. With this series of panoramas, his is one of the contemporary bodies of work that have contributed most to the revival of the panorama.

Partners and sponsors

With the support of Kolor | GoPro