Anne-Marie Filaire

Temporary security zone

Mucem, fort Saint-Jean—

Fort Saint-Jean Georges Henri Rivière Building (GHR) 320 m2

|

From Saturday 4 March 2017 to Monday 29 May 2017

Last days

The possibility of images

For more than twenty years Anne-Marie Filaire has been building a body of work that is dense, engaged, rigorous, and monumental. Her first series, made in the 90s in her native region of Auvergne, opened her to the subject of landscapes, leading her on a longterm personal and photographic quest.

In 1999, she headed to the Near East and East Africa. Israel-Palestine, Lebanon, Eritrea, and Yemen would be the terrain of her investigations for more than ten years. By moving through the most remote areas, she turns her gaze on the universal enormity of territories charged with history. Attentive to the scars and ravages of infinite time, she collects the signs searching for hints inscribed in the hollows. The missing images that she brings back call into question the possibility of representing un-representable spaces, borders, zones of contact and separation, between which she delivers the memory and the trace.

But how can we represent the reality of a landscape, when it is battered by the upheavals of interminable identity, territorial, and economic wars? How can we grasp the stigma of the past in the face of a contemporary history that is just being written?

Anne-Marie Filaire is not just an observer of the territories that concern her. Engaged in fieldwork, without ever backing away from the risks such an undertaking implies, she brings this experience to the limits of her intimate relationship with the landscape. Through the very act of taking the shot, the position and the rigor she imposes on her images, the perspective is constructed in all its severity and truth.

In this permanent movement between time and space, between history and the present, sounds an underlying violence. Far from the blinding moments of conflict, the distant horizons encounter the confinement of inextricable political situations.

Thus Anne-Marie Filaire offers us her own currency: that of the possibility of images, and with it a possibility of existence in invisible territories.

Fannie Escoulen Exhibition curator

My experience with landscapes began in the early 90s in Auvergne. I was subsequently involved in a major mission that the Ministry of the Environment implemented in 1992: a photographic observatory of the landscape, whose goal (documentary aim) was to record the evolution of landscapes over time, and to set up archives for the national territory. In an informal manner, I have taken this process of observation and documentation to a Middle East and the Red Sea troubled by history and violence.

Anne-Marie Filaire

Interview with Anne-Marie Filaire

|

Mucem (M) |

How does your work differ from that of a photojournalist or war correspondent? |

|

Anne-Marie Filaire (AMF) |

I did not go looking for situations in countries at war. I went to see landscapes, desert countries that spoke to me, that seemed to respond to the questions I was asking myself about the meaning of my life. A sort of blank page for understanding, aside from the people, conflicts, and everything that troubled me. I am an artist and sometimes I traverse the same terrain as the media—in war zones—but I do not work in the same timeframe. I settle-in long-term while the journalists relay information instantaneously. I have no obligation to return. While the approach is different, it was nonetheless the press, Libération, which first disseminated my work because the political dimension interested them. Before going into the field, there is work to do, preparations, and the images that I produce are highly constructed. The light and the violence are the beauty that I came looking for. |

|

M |

Beauty… in these hostile places? |

|

AMF |

If beauty exorcises violence, that’s what I wanted to photograph. Time is a fundamental aspect of your work. Evident, especially, in your series photographed between 2004 and 2007 in Jerusalem… During the construction of the wall in Jerusalem, I came regularly over three years, to do field surveys, to photograph the sites in a reoccurring manner, and to document this period when the space was closed. I settled-in over time. Remember, I was already doing this technical observation work on the landscape in France for the Mission de l’Observatoire Photographique du Paysage (photographic observatory of the landscape). The construction of the wall was a measure of the suffering, an indelible mark. |

|

M |

Why this fascination with borders? |

|

AMF |

The border- this is to know what belongs to me, what does not belong to me, where my place is and where it is not. |

Exhibition itinerary

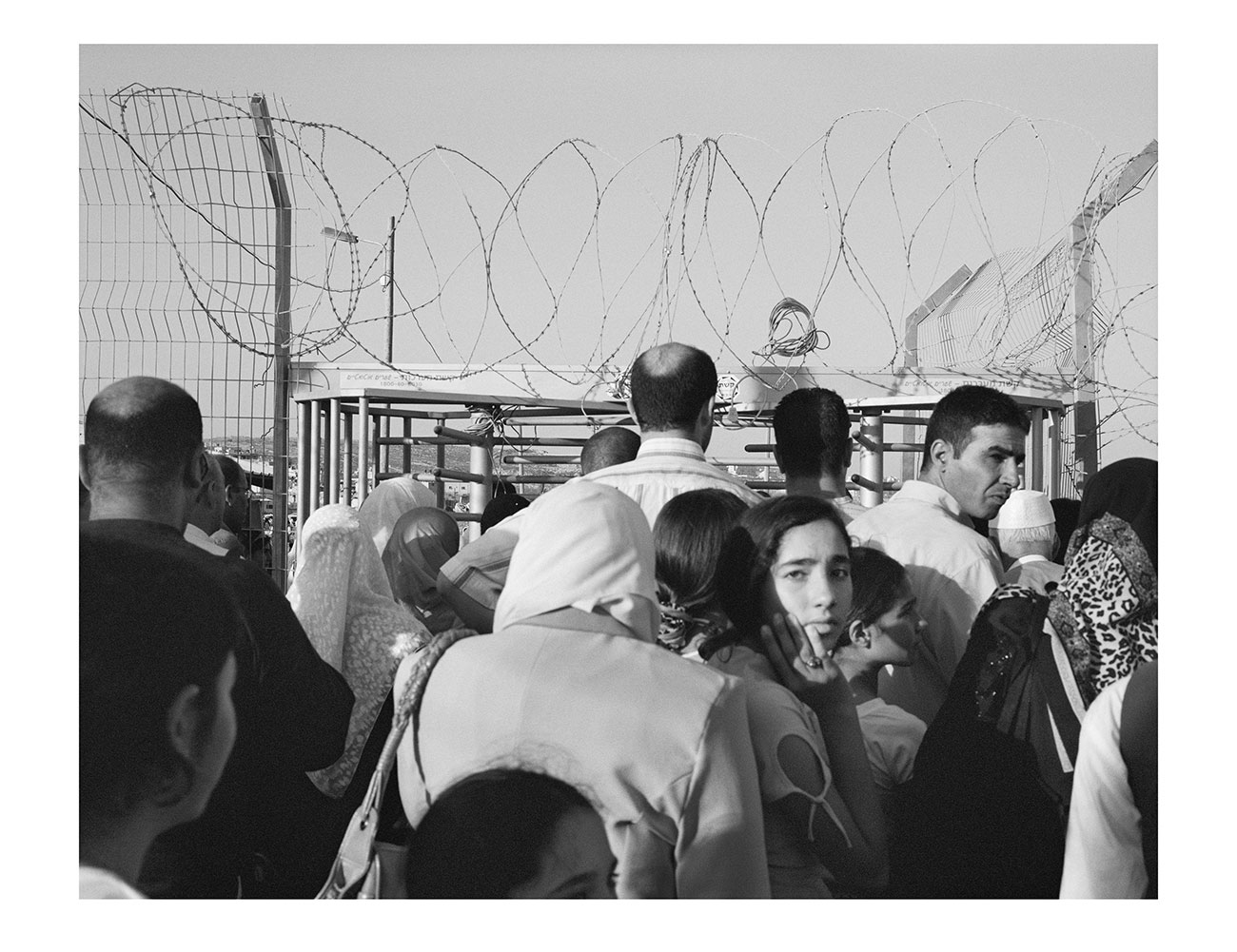

Israël—Palestine, 1999—2007

I came to Jerusalem for the first time in July 1999. That was where I wanted to begin my research in the Middle East, in this place where space and time meet. I wanted to understand this city independently of any faith or belief in a written text, rather like

the visual perception of a unique urban order, seeking to feel it rather than describe it.

Moving constantly throughout Jerusalem and its environs, I was able to read in the landscape the first traces of the occupation around the city. It was a little more than a year before the second intifada. And then I left Jerusalem; I needed to see it from afar, to

get away from it. I rented a car and went to Jericho, then Gaza, where I stayed alone for three days. From this period in my photography, the traces remain those of this departure, from this

frontier, from this possible interval. Gaza would have to be the strongest, most trying, image of this journey that remains for me today, inaccessible and missing and which turns the perception of space and time upside down.

I came back in 2004 and stayed in Palestine for three and a half months encompassing two trips, one in March and April, and then a second in October. The year 2004 witnessed the end of the rule of Yasser Arafat and the construction oxf the wall, and represents a period of extreme tension. Contact was broken between the populations and I found myself confronting a continual rupture in the landscape. The confinement materialised before my eyes. I worked roaming between the places and the people, passing from one world to the other. I was not seeking to represent this confinement but I was working within it. At that time I began making field surveys in the border areas around Jerusalem when passing

there. It was through this movement that my work was established.

Until 2007, I repeatedly photographed the same places to record their evolution and transformations, to find the landmarks. That’s when my photographs became panoramas. Working in these territories

demanded that I settle there long-term, to encounter this violence and the need to bear witness to it.

A succession of major political events inaugurated and accompanied the construction of the wall: seat of Yasser Arafat’s Mukataa.

He then departed for France seeking healthcare, but he would not come back alive.

2005: Unilateral withdrawal of Israeli settlers from the Gaza Strip and installation of new colonies in the West Bank and East Jerusalem.

In 2006, the Palestinian legislative elections conducted under strict international supervision brought Hamas to power. I worked in Nablus in April of that year.

Yémen—Erythrée, 2000—2005

During the same period, I travelled in other Middle East countries like Yemen, in 2000, 2001, 2003 and 2005. Initially, I was motivated to go to Yemen by my desire to discover a hidden country, closed off from the eyes of the world. In the founding texts, this is

the country where paradise on earth is found. To travel in Yemen, is to travel back in time. Following the events of September 11, 2001 in the United States, one of my flights to Yemen was suspended.

So I made a quick decision to go to Eritrea. I went to

Asmara on September 19, 2001 for a two-month trip in Eritrea and Yemen where I had stayed the previous year.

My work was subsequently situated between these two countries, geographically close yet separated by the Red Sea, whose history and concerns were quite different, particularly at that time.

During my stay in Eritrea, I lived in Asmara and travelled around the country. My photographic work reflects these landscapes. I particularly wanted to work along the Ethiopian border south of

the Danakil Desert, near Assab. For that I contacted the United Nations Mission (UNMEE), which helped me travel to these places by offering flights and logistical support.

My first time in Assab I tried cross the Temporary Security Zone, a highly volatile and thoroughly mined 25-kilometre-wide border area. I could not penetrate it and I was driven back to km 44, escorted by the officer in charge of political affaires and two Kenyan

soldiers. The political situation was difficult at this time and the week before, ten journalists from the independent press had been arrested and imprisoned

I came back on 12 and 13 November armed with a press card loaned by the Untied Nations. I was thus able to enter this space where I made a hundred images.

I also made pictures at the port of Assab, which was entirely deserted at that time.

The port entrance was prohibited but I had a contract from CARP (Cultural Assets Rehabilitation Project) issued by the state of Eritrea authorising me to photograph the interior of the theatre of Asmara and other historic sites contributing to the promotion of

Eritrean heritage.

Southern suburbs of Beirut—South Lebanon, 2006

On 12 July 2006, Lebanese Hezbollah abducted two Israeli soldiers in the border area intending to prompt an exchange of prisoners.

The very same day, Israel launched an offensive throughout Lebanon and destroyed the southern part of the country, Baalbeck, and the Dahiyeh district in Beirut.

I returned to Lebanon during this singular post-war period, wanting to see the consequences of this act and seeking simply to understand.

My work was carried out during this transitional phase, from the end of the war with Hezbollah’s celebration and the speech by Nasrallah in the southern suburbs of Beirut, followed by the arrival

of the different contingents of the United Nations, the withdrawal of the Israeli army and the deployment of the Lebanese army in South Lebanon. I photographed Dahiyeh, the southern suburbs

of Beirut, and I travelled in the south of the country. I stopped in Sawaneh, a village in Jabal Amil, South Lebanon. There, I focused my work on a house that had been hit by six shells on the eleventh day of the war.

Jordan-Syrian border, 2014

“The photographs of Azraq, a Syrian refugee camp located in the middle of the desert in northern Jordan, are the last from my travels in this region of the world. They were taken in June 2014 when

Syria had just completely closed its borders.” Anne-Marie Filaire

“Azraq, it’s the birth of a city. In the midst of what could be considered nowhere, these rows of metal barracks are reminiscent of other settlements, other eras. The Azraq refugee camp in Jordan opened in 2014 intending to receive more than fifteen thousand

people. Brand new, it welcomed the first refugees from Syria while Anne-Marie Filaire was there. A virgin place of survival, but pre-designed to order life and behaviour. A temporary place built to last.”

Géraldine Bloch

Biography of Anne-Marie Filaire

From her first series initiated in 1993 in her native region of Auvergne, to her work in the volatile regions of the Middle East, Anne-Marie Filaire has been building a dense, engaged body of work, as rigorous as it is lyrical.

Her photography, oriented towards the landscape, focuses particularly on the so-called “borderlands” and “buffer zones”, in the Middle East, Southeast Asia, East Africa and Europe.

In 1999, she began a parallel project that took her to the Near East (Israel-Palestine), devoted to observing spaces as physical entities, charged with history over time. For nearly ten years, she continually roamed these territories, documenting them like a geographer, collecting the traces of time in these political landscapes in flux. Her research continued in other countries marked by their history and conflicts, such as Lebanon, Yemen, Eritrea

and Cambodia.

Continuing her work in the Arab world in 2007, she focused on adolescents, their environment and intimate spaces, in the United Arab Emirates and then in Palestine (Gaza). Gradually, this quest

drew her to moving images and she conducted filmed interviews with youth in the Middle East (Egypt, Algeria), in the context of the

revolutions. In 2012, she concluded this research with an important series on armoured doors in Algiers.

Her final investigations in the Middle East brought her to the Jordan-Syrian border in 2014 where she photographed the Azraq Syrian refugee camp.

Exhibition curator

A graduate of the Ecole Nationale Supérieure de la Photographie

in Arles in 2000, Fannie Escoulen is an independent curator specialising in photography.

Deputy director of BAL in Paris from its creation in 2007 until 2014, she was commissioner of the monographic exhibition of Antoine d’Agata “Anticorps”, presented successively at the Fotomuseum (The Hague), BAL (Paris), Forma (Milan) and La Termica (Malaga). She also curates the exhibition of Stéphane Duroy presented

at BAL from January to April 2017.

Artistic director for the Levallois Prize for young international photographic talent since 2015, she is particularly interested in young photographers and is currently preparing an exhibition at Fotomuseum in Antwerp on the new Spanish photographic scene.

In addition, she collaborates regularly with publishing houses as an editorial director for monographs (Antoine d’Agata, Anne-Marie Filaire, Stéphane Duroy…).

Scenography

A modular scenography

The scenography was designed by Olivier Bedu, Struc Archi.

A series of units that fit together in various configurations was designed for use in seven different exhibitions including “Anne-Marie Filaire: Zone de Sécurité Temporaire (Temporary Security

Zone)”. This ensemble is the basis for a construction game enabling the creation of scenographic configurations adapted specifically for each exhibition.

The design of the units borrows from the language of decor. The structure, in wood, is partially visible, like scaffolding.

This work of unveiling the structure avoids the monolithic effect of picture rail and moves the project forward by transforming the elements.

The scenography creates depth of field; the gaze passes through the unit, inviting circulation into the following space.

Struc Archi

Struc’ Archi is an architectural firm (EURL) founded in 2002 by Olivier Bedu, architect and director. The agency is located in the centre of Marseille. Its speciality is developing architecture on a uniquely human scale: extensions, houses, urban design, fairground structures, and scenography.

The role of scenography is to know how to take diverse elements—illustrations, paintings, and multimedia—and create a cohesive ensemble. The firm seeks to create scenography where the foundations, bases and picture rails are all elements of architecture and design. This vision of space as a whole, allows the firm to create spaces that vary both visitors’ points of view, and their patterns of circulation.

An exhibition brings together objects and a way of thinking. Scenography is not viewed by the firm as just a support for the works presented, but rather as an element of dialogue. The principle idea of scenography nurtures and refines the expectations and intentions of the curators, like those of the museum: placing the ideas of the firm in dialogue with those of the other stakeholders in the project. The collaboration actually becomes the space that brings the project to light, creating for the public a place for strolling and wandering, to accompany an appetite for culture.

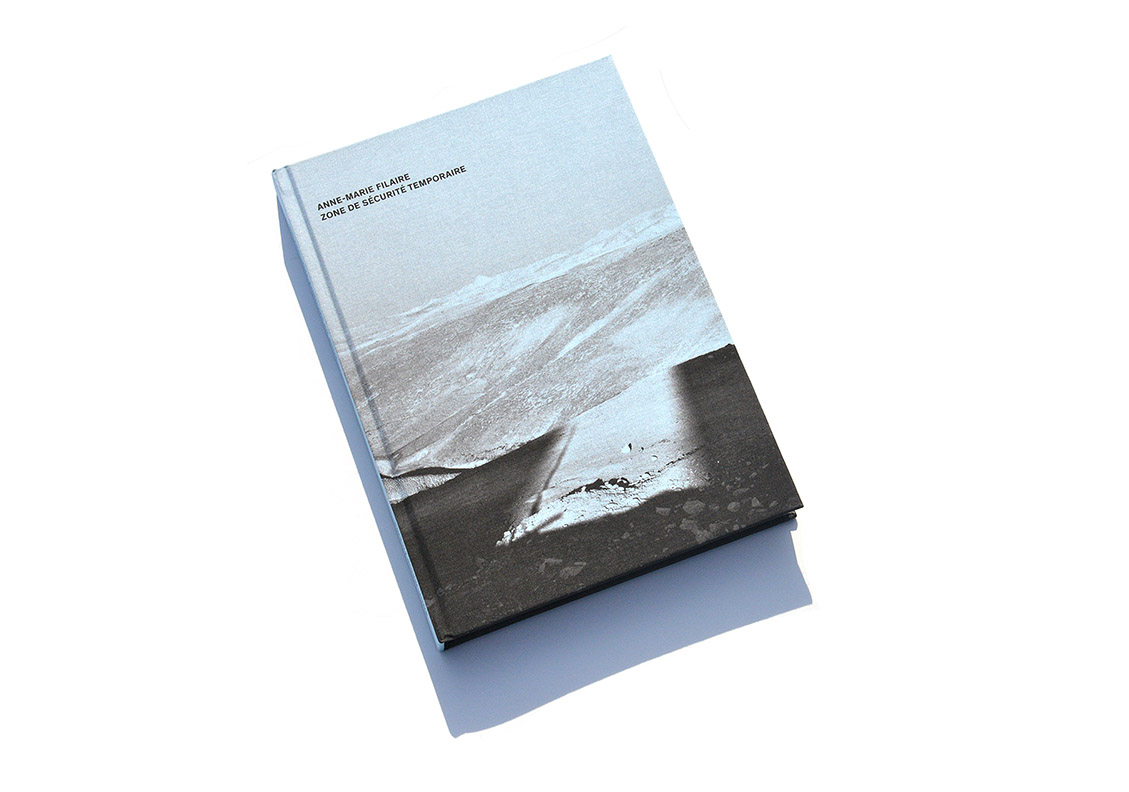

Publication

Partners and sponsors

In partnership with Les Inrockuptibles